Ink Monkey salutes the genius of iconic publisher Aloes Books, and co-founder Jim Pennington, whose samizdat publications during the 1970s and 1980s included works by Thomas Pynchon, Bob Dylan, William Burroughs, Patti Smith and Kathy Acker.

Ink Monkey salutes the genius of iconic publisher Aloes Books, and co-founder Jim Pennington, whose samizdat publications during the 1970s and 1980s included works by Thomas Pynchon, Bob Dylan, William Burroughs, Patti Smith and Kathy Acker.

In the mid-1960s a revolution took place in British publishing. This venerable industry, which had barely changed or needed to change since the setting up of the great publishing houses in the Twenties, Thirties and Forties suddenly found itself under attack as a number of maverick writers, radicals and alternative entrepreneurs seized the means of production and ushered in the golden age of the small presses.

Today, when much of our literary culture is shaped, defined and digitally delivered to us by large conglomerations, the notion of the literary lone wolf, sitting in a kitchen, or in the back room of a bookshop, or a rural or urban commune or squat and printing a book or magazine at a table is as remote as the 1960s itself.

One such press that set up was Aloes Books, founded by the printer Jim Pennington and two poets from the alternative poetry scene, Allen Fisher and Dique Miller.

“I was in Brighton in 1967, the year Bill Butler opened his Unicorn bookshop, and I became part of the scene around the shop,” says Pennington. “Bill was more than just a bookseller — he was a presence.

Through the shop, and the wider Brighton arts scene generally, I met a lot of interesting and inspiring people, people like Nick Heath and Jim Duke, well-known and active anarchists whose enthusiasm and spirit-warming influence had a great effect on me, and also the mural artist John Upton, who made me think more visually back at a time when street decorations, murals were the new thing.

What was good about Unicorn was the fact that the people who worked there, and some of the people who went there, had a harder, more political edge to their thinking. They were hippies but not the bells-and-kaftans type. Each visit to the shop was an exploration, because I would often visit not specifically looking to buy something but looking to be guided to something, often American which you couldn’t get easily elsewhere.”

Unicorn helped Pennington along the road to becoming a printer/publisher by allowing him to experiment on their machine. It was the start of a passion for the printed word that remains with him to this day.

“Around this time I also met the two people I would go on to start Aloes with. Dick Miller, was a poet from Birmingham who used drugs but wasn’t in any way a hippy so I ended up calling him a Beatnik. Allen Fisher, another poet, was a man who was already becoming a bit of a prime mover on the small press publishing scene and had been active in publishing even before we started working together.”

Fisher set up his Edible Magazine in 1968, printing his own work and that of others onto edible rice paper, shortcake and other consumable material using cochineal food colouring. The editions would sometimes have poisonous supplements. That same year Jim Pennington moved up to London to do a BA degree at the North-West Poly in Kentish Town followed by a London College of Printing course at the Elephant & Castle, working towards a Diploma in Book and Periodical Production. For a man primed in the pleasures of the alternative bookshop scene, his first task was to source out, and in some cases reacquaint himself with, the more radical book stores.

All Horses Have Feathers, an early collaboration

between the three founders of Aloes

“It was at Freedom where you learned where the next march was, and, as importantly, who to stand next to at it. This was the time of great groupings and political splinterings. I got involved in groups, but usually not for long since I had the attention span of a butterfly, and I could rarely keep up with what was being said anyway.

But I did go on a few of the marches. At a Vietnam march – not the Grosvenor Square one – I remember a group of us London anarchists were coming down the Strand and we peeled off, as we tended to do, under the black flag banner and ended up coming into Whitehall from a side street bearing down on a Guardsman with a large sword. He came at us with the weapon raised and we actually surrounded him, jeering and chanting with taunts of “fascist bastard” but when re-inforcements came rushing out waving their swords as well, we beat a hasty retreat, disappearing into the crowd of tourists who must have wondered what the hell was going on.”

By 1970, Fisher, Pennington and Miller had got as far as registering a business name and setting up an account and had come up with a name and a logo. Calling the venture Aloes was Dick Miller’s idea – “something to do with bitter, I think,” says Pennington – and it was Miller who drew the logo, a book with a bite out of it, which was a passing nod to Fisher’s Edible Magazine. Jim Pennington promptly had a tattoo done of the logo which he proudly sports to this day. “I won’t show where,” he says, mysteriously.

Quite a few other small presses were by this time up and running: Trigram Press was set up by the poet and book designer Asa Benveniste who published works by a number of poets, amongst them George Barker, Tom Raworth, Lee Harwood, Jeff Nuttall and Ivor Cutler. It also published work by the experimental writer B.S. Johnson. Fulcrum Press, Stuart and Diedre Montgomery’s imprint put out a number of titles key to the British poetry revival of the time, including editions by Basil Bunting (a man whose reputation was rescued by the small presses), Ian Hamilton Finlay, Roy Fisher, the ubiquitous Nuttall and Tom Pickard. Iain Sinclair would shortly be getting going with his Albion Village Press. Tom Raworth had established Goliard in 1965, along with Barry Hall, bringing to the British market a number of contemporary American poets for the first time. Such was the success of small press publishing at this time that Goliard was eventually assimilated into the traditional publishing house of Jonathan Cape, becoming Cape Goliard, publishing work by D.M Thomas, William S. Burroughs and others.

“One aspired to publish books like Trigram or Fulcrum or Cape Goliard, but really they were a little bit more mainstream than us. Some of their books had wraps, for heaven’s sake, and they could usually afford more effects than we could ever muster. We’d been more influenced by some of the American small press publishers, in particular the work that various members of The Fugs had put out. Ed Sanders ‘Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts’ was a wonderful thing to behold, lots of great stuff in it by people like Artaud, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Berrigan, Mailer and, of course, Tuli Kupferberg himself. We also kept a close eye on the work that Opal L Nations, a man who in a former life had been an R ’n’ B singer, was doing and also were impressed with Peter Finch’s ‘Second Aeon’, which was a magazine published out of Cardiff that put out work by Bob Cobbing, Iain Sinclair, Ginsberg, Bukowski and others. Also, there was a great publisher called Beau Geste. They were doing Fluxus poetry and the more arty stuff that turned the books into objects in their own right. They ran out of a commune in Collumpton and had the kind of set up that Bill Butler tried to emulate when he closed up shop on Unicorn and moved down to Wales.”

The Unicorn bookshop also ran a publishing venture and ran into trouble when it published the notorious pamphlet by J.G. Ballard ‘Why I Want To Fuck Ronald Reagan’ in 1968. Like the later, more famous Oz magazine trial of 1971, the case quickly descended into one where lifestyle was in the dock, not the poor bookseller who was charged with handling obscene material. ‘Is this not the meanderings of a dirty and diseased mind?’ asked the prosecuting council, and was surprised when expert witness, BBC radio producer and poet George Macbeth answered him by saying that if the work ever became available for broadcasting he would love to use it.

“Just before Aloes got going I found a job in a paper warehouse in Covent Garden,” continues Pennington. “I bought some stock off them for a knock-down price after there was a fire and some beautiful green Glastonbury ledger laid paper got smoke damaged. We used this as a long fold-out for Max Blagg’s epic ‘From Here to Maternity’.

“Just before Aloes got going I found a job in a paper warehouse in Covent Garden,” continues Pennington. “I bought some stock off them for a knock-down price after there was a fire and some beautiful green Glastonbury ledger laid paper got smoke damaged. We used this as a long fold-out for Max Blagg’s epic ‘From Here to Maternity’.

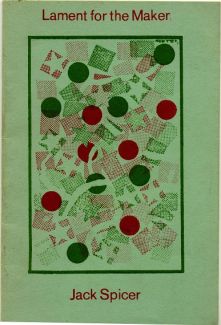

“The first books we published were ‘After Lorca’ and ‘Lament For The Maker’, both by Jack Spicer who was an American poet associated with the San Francisco Renaissance Movement. That would have been in 1971. I used to go up to the Arts Lab, first when it was in Earlham Street and then when it moved to Robert Street (where Ballard’s ‘Crash’ show was galleried) and later Prince of Wales Crescent in Camden where they let me use their small offset litho machine. It was a great machine, easy to run and difficult to break. They let me have a free run of the place, because they knew that I could use the machine properly. Then I got a job with a printer in a small offset print unit in Hammersmith and did some books there. I spent an awful lot of time staying late at the office. On ‘Lament For The Maker’, the paper plates broke up and the ink was a bit too tacky which created a sort of peeled-off effect on some of the copies, but it was an unexpected result that I actually liked.”

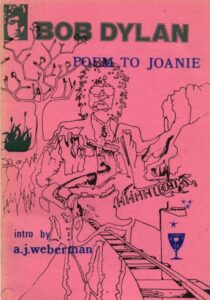

Another early title was Bob Dylan’s ‘Poem To Joanie’, which reproduced liner notes of In Concert Volume 2, a Joan Baez album, which Dylan had written in poem form. In their enthusiasm to see the material published Aloes overlooked the small matter of rights clearance, but no-one objected. After all, this was the golden age of the bootleg. Jim Pennington wrote to the Dylanologist AJ Weberman and used the letter he got back as an introduction. The title sold so well that Aloes put out a further Dylan title, ‘Eleven Outlined Epitaphs’, which drew together all the epitaphs Dylan had written for the sleeve notes of The Times They Are A Changing album (not all had appeared on the UK version of the album cover). There was an introduction by Stephen Pickering and more notes from Weberman.

Another early title was Bob Dylan’s ‘Poem To Joanie’, which reproduced liner notes of In Concert Volume 2, a Joan Baez album, which Dylan had written in poem form. In their enthusiasm to see the material published Aloes overlooked the small matter of rights clearance, but no-one objected. After all, this was the golden age of the bootleg. Jim Pennington wrote to the Dylanologist AJ Weberman and used the letter he got back as an introduction. The title sold so well that Aloes put out a further Dylan title, ‘Eleven Outlined Epitaphs’, which drew together all the epitaphs Dylan had written for the sleeve notes of The Times They Are A Changing album (not all had appeared on the UK version of the album cover). There was an introduction by Stephen Pickering and more notes from Weberman.

“We really felt in those early days that what we were doing was being appreciated by people. People liked the way the books looked and the feedback we got from shops was terrific.” It was something Aloes did because they were passionate about the writing and passionate about publishing. “We wanted, and our readers wanted, books that were different from the boring old books you found on the shelves at Foyles. But the rewards were more spiritual than financial.

“You had a limited market in terms of the numbers of shops that would take a title. You’d wend your way around London dropping off sale or return copies at bookshops and you’d go back a month later and hopefully pick up some money.

It helped that Aloes had people like Dylan, and later William S. Burroughs and Patti Smith and Thomas Pynchon and the sales figures could on occasions be quite healthy. A key shop like Compendium would be a terrific help – they knew the material, they would always display it well and they knew how to sell it.”

It helped that Aloes had people like Dylan, and later William S. Burroughs and Patti Smith and Thomas Pynchon and the sales figures could on occasions be quite healthy. A key shop like Compendium would be a terrific help – they knew the material, they would always display it well and they knew how to sell it.”

Being able to produce a short print run – many Aloes titles started off with a run of 100 – and being canny about the titles by name authors which would start off with printings of one thousand was the trick that worked.

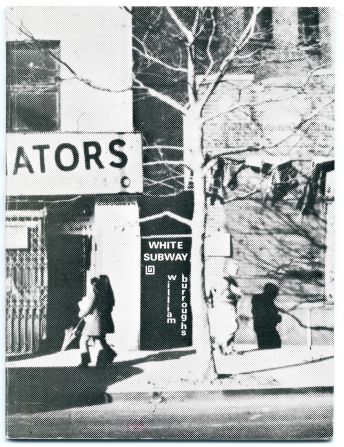

“We were interested in putting together a collection of the many pieces William Burroughs had contributed to small magazines. How to get hold of him? Eric Mottram, who was an influential critic and poet, happened to have Burroughs’ phone number. So we just rang him up and suggested the idea. We published ‘White Subway’ in 1973 and went on to reprint it five times with each reprint being no less than 1000. When we got to the fourth reprint I couldn’t make new plates (the negs had been lost), so there are two third editions, one in silver, and one in black and white. I can’t remember which came first. It has a cover I am very pleased with: the photo of the exterminators’ office is flipped so a black doorway would be on the right and become a subway entrance, I repasted in the shop lettering. The image wraps around the entire cover, something common now but very unusual then.”

“Authors tended to see it an Aloes book as a venture that would enable them to reach an audience and have some copies instead of royalties rather than a way of pocketing some upfront cash. But I gave Burroughs a cheque for £50 for signing the limited editions. About two years later I got a letter from him enclosing the returned cheque and saying that he’d forgotten to pay it in and the bank wouldn’t honour it as it was out of time. Could I write him a new one? I was in New York later that year so I gave him the cash … much simpler.”

The years of the early 1970s were not kind to the arts or arts sponsorship. The establishment line, particularly under the Conservative government of 1970-74, was that the freedom of the sixties had been a hedonistic and indulgent mistake, one not to be repeated. The massive economic downturn put paid to any excesses anyway and, as ever, it was the operations on the margins that suffered the most. The optimism and the spirit of adventure of the decade George Melly would memorably describe as “an extraordinary and seductive aberration” was over. The once chosen retreat to ‘inner space’ became unavoidable. The alternative, anarchic, and libertarian ventures one by one started to shrivel up and die. Many small presses went out of business.

“We never ran Aloes with the expectation that it would be a profit-making venture,” says Pennington. “We weren’t doing it to make money – and that’s always a useful approach in my experience when dealing with books.”

But the advent of punk, which found its first stirrings in the UK in London in early 1976 produced a new generation of people interested in alternative publishing. Punk’s proudly DIY approach, with its emphasis on access and enablement, led to a prolific, almost uncontrolled outpouring of printed material in the form of fanzines and self-produced books, a sort of Xerox version (anti-corporate) of the Amazon Kindle Direct programme today which (some say unfortunately) enables anyone to publish a book. During the 1960s and early 1970s there had also been hundreds and hundreds of alternative literary and poetry periodicals, many of which are lovingly listed in John Noyce’s ‘Directory of British Alternative Periodicals, 1965-74’ (Harvester Press) and the same approach, style and even similar fast, cheap printing link early 1960s mimeographed publications like Jeff Nuttall’s ‘My Own Mag’, which ran for seventeen issues between November, 1963 and September, 1966 and introduced many British readers for the first time to the work of William S. Burroughs, and those early punk fanzines of the 1970s, such as Mark Perry’s ‘Sniffin’ Glue’ which trail-blazed punk.

“After seeing a Telegraph books reading with, amongst others, Patti Smith, we corresponded and she did a book with Tom Verlaine for us – ‘The Night’. It took a while to design and print but it was ready just in time for her first ever concert in England – at the Roundhouse in 1976. Punk was around the corner, though we didn’t know it. That beautiful little16-pager really did go on to sell a lot copies, at least 8,000 over several reprints.

“She had another book out the next year, ‘Ha! Ha! Houdini’ which the Gotham Book Mart published in New York in 1977. That book was only available on import in places like Compendium and was ridiculously expensive. Ripe for bootlegging. Then Patti was in London and I arranged to meet her at Compendium with the money for the signed edition of ‘The Night’. I noticed about 50 copies of the bootleg edition sitting on a display rack right next to where she was standing. She noticed them as well. ‘What are they?’ she demanded. ‘Hand them over to me.’ I thought Compendium were going to get yelled at something rotten, but instead she scooped them all up and furiously began signing them – she did the whole lot. The occasion could have gone wrong again because she flatly refused to take a cheque from me – money only – and Nick Kimberly had to come to my rescue and lend me some cash out of the till.”

“She had another book out the next year, ‘Ha! Ha! Houdini’ which the Gotham Book Mart published in New York in 1977. That book was only available on import in places like Compendium and was ridiculously expensive. Ripe for bootlegging. Then Patti was in London and I arranged to meet her at Compendium with the money for the signed edition of ‘The Night’. I noticed about 50 copies of the bootleg edition sitting on a display rack right next to where she was standing. She noticed them as well. ‘What are they?’ she demanded. ‘Hand them over to me.’ I thought Compendium were going to get yelled at something rotten, but instead she scooped them all up and furiously began signing them – she did the whole lot. The occasion could have gone wrong again because she flatly refused to take a cheque from me – money only – and Nick Kimberly had to come to my rescue and lend me some cash out of the till.”

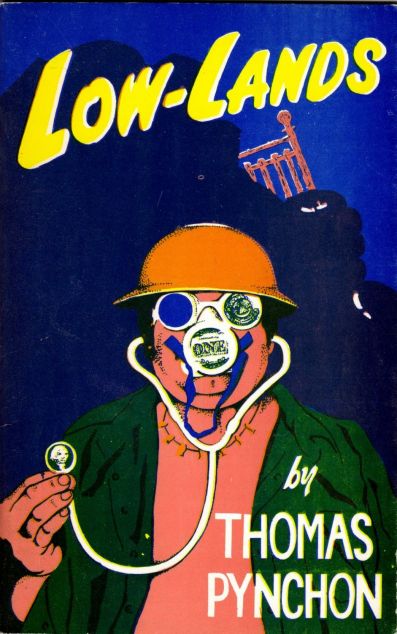

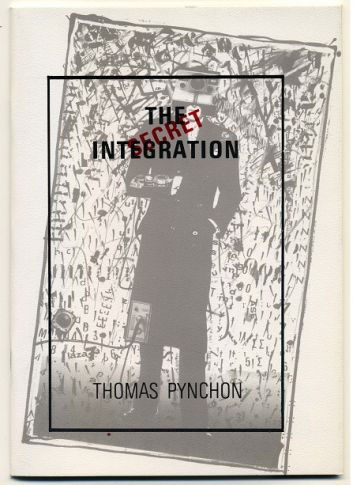

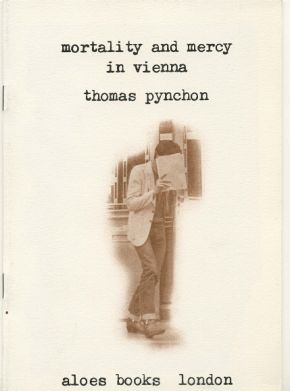

The same year that The Night, came out Aloes published the first of four Thomas Pynchon titles, a loosely themed group as it turned out, early short stories that had been published in various university magazines and newspapers. Gravity’s Rainbow had been published in 1973 and its brilliance immediately recognised. Pynchon’s popularity suffered no harm from the fact that, like J.D. Salinger, he was a recluse. And there was, consequently, an ever-increasing demand for work either by or about Pynchon. Mortality & Mercy in Vienna was followed by Low Lands (1978), The Secret Integration (1980) and Small Rain (1982), most quickly going into reprint after their initial runs sold out.

“The general view is that we bootlegged these titles, but in fact in every case except the last we had cleared the rights with the copyright holder. We paid $75 to publish Mortality & Mercy, the money going to the university magazine that originally published the piece. Strangely, that piece of work was the only one of the four not included in Slow Learner, the book that collected the stories and that was published in Britain by Jonathan Cape, the book in which Pynchon complained that the Aloes deals had been done without his authority.

“We did a good job on those titles and put fantastic covers on them, including one designed by Jake Tilson. On Mortality & Mercy in Vienna I used a photograph of a man holding up some papers to cover his face and just about everybody assumed it was Pynchon. In fact it was Max Blagg, another Aloes author, coming out of a post office and holding up a large envelope to hide behind. We sold the least copies of Low Lands, primarily because the cover was an absolute nightmare to produce and I didn’t want to have to do it twice. The solid blocks of colour were achieved by running the cover through a small litho machine four times. It was a painstaking job.

“We did a good job on those titles and put fantastic covers on them, including one designed by Jake Tilson. On Mortality & Mercy in Vienna I used a photograph of a man holding up some papers to cover his face and just about everybody assumed it was Pynchon. In fact it was Max Blagg, another Aloes author, coming out of a post office and holding up a large envelope to hide behind. We sold the least copies of Low Lands, primarily because the cover was an absolute nightmare to produce and I didn’t want to have to do it twice. The solid blocks of colour were achieved by running the cover through a small litho machine four times. It was a painstaking job.

“For each book we contacted Pynchon’s agent and although we had a half-hearted complaint, there were never any cease-and-desist calls or heavy knocks on our doors at night.”

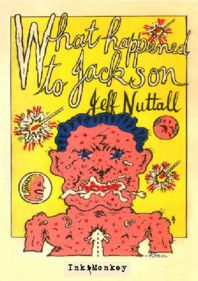

Another important literary figure that Aloes had started working with was Jeff Nuttall, whose talents as a poet, writer, artist, musician, anarchist, agitator and all-round father figure of the counter culture had most prominently come to recognition with the publication of Bomb Culture in 1968. Aloes had published a slim volume of poetry and drawings, The Foxes Lair in 1972 and in 1979 produced one of the finest books that Aloes published, What Happened To Jackson, a bizarre murder-mystery novella all set in the surrounding areas of Leeds where Nuttall worked (as a senior art lecturer at Leeds Polytechnic.)

“In the 1960s Jeff Nuttall’s presence was felt everywhere — from Better Books where he put on “The Peoples Show” happenings, through poetry readings and of course through the enormous impact that his book Bomb Culture had had when it came out in 1968. And his My Own Mag had been tremendously important in bringing the experimental work of William Burroughs to a wider audience.

“Jeff had some rather graphic, rather beautiful nude photographs that we used instead of a title page in What Happened To Jackson. Given the book’s content, they were part and parcel of what the book was about. Jeff was astonished that we were able to reproduce them since back then photographs tended to be printed one way – on glossy art paper – and words were printed on rough wove paper, which was thicker because publishers wanted their books to look more substantial. Book paper was sold by volume and not weight. So 80gsm book paper was thicker than your average 80gsm ordinary paper, and bought according to volume – 18vol., 20 vol., 24 vol. But I knew if we screened them properly and compensated for the paper surface then they’d print up perfectly. Which they did and it is one of the titles I am most proud of, not least for the production values that we gave it.

“Jeff had some rather graphic, rather beautiful nude photographs that we used instead of a title page in What Happened To Jackson. Given the book’s content, they were part and parcel of what the book was about. Jeff was astonished that we were able to reproduce them since back then photographs tended to be printed one way – on glossy art paper – and words were printed on rough wove paper, which was thicker because publishers wanted their books to look more substantial. Book paper was sold by volume and not weight. So 80gsm book paper was thicker than your average 80gsm ordinary paper, and bought according to volume – 18vol., 20 vol., 24 vol. But I knew if we screened them properly and compensated for the paper surface then they’d print up perfectly. Which they did and it is one of the titles I am most proud of, not least for the production values that we gave it.

“I also managed to get the artist and film maker Jeff Keen to do the cover, and he came up with a wonderful image. It was perhaps a little bit more colourful than Jeff was used to, though.”

Things Slow Down at Aloes

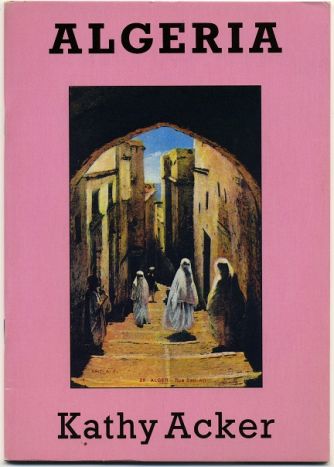

As the 1980s progressed, Aloes output slowed down. The publishing landscape altered, starting to take on the shape that is has today, where a small number of conglomerates dominate, and within them the Sales and Marketing teams are the real power elite. The slow decline of the independent bookseller also began, with even Compendium closing its doors in 1991. The rise of Amazon was not too far around the corner. At some point also booksellers started asking Pennington to print the titles with perfect bound covers (i.e., with spines) so they could be displayed spine text out. It all started to get, well, corporate and uninteresting. Other things started demanding time as well, such as marriage, children and being part of a printing co-operative, Lithosphere, which he had helped set up after his then employers, the campaigners War On Want, had been forced by the charity commissioners to hive off their printing operation because it was doing outside commercial work and they saw this as being in contravention of a charity status. But still some gems appeared. There was a fine work by the New York performance artist David Wojnarowicz, “Sounds in the Distance” in 1982 and experimental novelist Kathy Acker contributed Algeria: A Series of Invocations Because Nothing Else Works in 1984. The final title, Max Blagg’s Licking Up the Fun appeared in 1991.

Today, the rise of digital publishing, downloading and internet shopping has simultaneously opened up new and innovative opportunities that Pennington and his contemporaries could or would have scarcely dreamed of during their prime. But setting aside the usual criticism of this new nirvana – the charge that quality control is largely none existent – the mechanism of production and distribution makes for a remote and colourless culture, and freedom to express is inevitably owned, controlled, and regulated by the faceless ‘brands’ that own the distribution platforms.

Today, the rise of digital publishing, downloading and internet shopping has simultaneously opened up new and innovative opportunities that Pennington and his contemporaries could or would have scarcely dreamed of during their prime. But setting aside the usual criticism of this new nirvana – the charge that quality control is largely none existent – the mechanism of production and distribution makes for a remote and colourless culture, and freedom to express is inevitably owned, controlled, and regulated by the faceless ‘brands’ that own the distribution platforms.

“I reckon that it is in the blogosphere that you find the nearest thing to those small presses from the 1960s and 1970s. A blogger has that ability to see his work go beyond his laptop and out into the world, in much the same way that forty years ago someone with an articulate vision and a typewriter could reach their audience as well.”

In spite of the hiatus, it is highly likely that Aloes will be back — if indeed it ever went away — since Pennington is too full of good ideas and too fond of Aloes to fully let it go. Indeed a future project is already in motion: a version of Georges Bataille’s scandalous Madam Edwarda, translated fittingly by Max Blagg. It will quite possibly be a work of “hard, clinical porn, a little like those 1960s porn books that were knocked out in the basements of Soho sex shops. It will have to be typed on a machine from that era as well. Yes, I know there are typewriter fonts on a computer these days but they are all wrong. We don’t want the type perfectly aligned. We don’t. That just wouldn’t be right.”

Unexpected non-alignment? Now that’s the sort of serendipity you just can’t find in the digital world.

Images were supplied by Jim Pennington who is a printer and small press publisher trained at London’s North-Western Polytechnic and the London College of Printing. Over the course of his long career, he has worked as a print room and production manager first for the British Safety Council (1971–75) then for the anti-poverty charity War on Want (1975–79) and then for the Lithosphere Printing Co-operative (1979–1991), among others. In parallel, Pennington ran Aloes Books, the influential small press he established with the poets Allen Fisher and Dique Miller. Aloes Books has published key works by Kathy Acker, Thomas Pynchon and William Burroughs, among many others. Pennington’s work was featured as part of Islington Exhibits 2013, a series of exhibitions enabling the public to view artists works in hitherto unexplored settings. What Happened To Jackson by Jeff Nuttall is available from Amazon.

I really enjoyed this history that you put together of Aloes books. It bought back memories of collating pages in front of the fire in the living room in North London. The weekends at the British Safety Council print shop, and many more recollections. It was also fun to see one of the illustrations I did which ended up on the Poem to Joanie cover. Jim had graciously suggested that we add Seola to the Aloes name as a way of acknowledging my work. This time period also encompassed our traveling to Joujouka in Morocco which was worthy of a whole book on it’s own.

I also enjoyed your comment about joining many groups at that time. It was a fast paced era, and I only recently started to put things in chronological order with dates affixed. Anyway.

Best Wishes.