It was seeing one of our American colleagues recently describing them as “a group of bootlegged Thomas Pynchon chapbooks printed in the UK” that brought back to mind a delightful piece of original research carried out by Florina Jenkins for a London Rare Books School essay. To set the record straight, here is a pared-down version of her findings.

It was seeing one of our American colleagues recently describing them as “a group of bootlegged Thomas Pynchon chapbooks printed in the UK” that brought back to mind a delightful piece of original research carried out by Florina Jenkins for a London Rare Books School essay. To set the record straight, here is a pared-down version of her findings.

In Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Oedipa Maas, starting with a pirated paperback, attempts to find and decode the definitive text of a mysterious Jacobean revenge play. Inspired by Oedipa’s labyrinthine investigations, I embarked on a quest in search of Pynchon’s own “pirated editions.” The Clifford Mead bibliography (1989) lists six “unauthorized editions” of early Pynchon stories – elsewhere calling them “piracies” – all published in England between 1976 and 1983. Four of these, the subject of the present piece, were published as pamphlets by Aloes Books, a London-based small independent press.

Thomas Pynchon (b. 1937) is one of the most remarkable contemporary American novelists – the “most monstrous talent in the post-war West” according to Time Out. Famously, he shies away from the media, grants no interviews, no photo opportunities, and has made no public appearances beyond the celebrated bag-over-his-head cameos in The Simpsons.

With almost no clues, I started my sleuthing mission in a friend’s bookshop, where I was delighted to find some of the Aloes pamphlets. Originally published in American periodicals between 1959 and 1964, these stories were not readily accessible until the appearance of Pynchon’s Slow Learner in 1984, when the intensely private author accompanied their release with an extraordinary autobiographical introduction. He describes the painful experience of re-reading his earliest writing:

“My first reaction … was Oh my God, accompanied by physical symptoms we shouldn’t dwell upon.” He calls them “goofy and ill-considered,” embarrassing, defective. This harsh verdict has never been shared by his devotees, who loved the stories and their marvellous and memorable characters – Pig Bodine, Dr. Slothrop, Irving Loon and many more. The question remained, why was Pynchon now presenting these pieces if he didn’t like them? The answer was almost certainly the existence of the “pirated” editions. Three of the five Slow Learner stories had been published by Aloes, while a fourth had also appeared under a UK imprint. Perhaps better to have a controlled edition prefaced by an apologetic introduction.

Having studied the pamphlets I decided to seek out the man whose name I found on one of them: Jim Pennington. Through some fortunate (some may say Pynchonesque) circumstances, I found and obtained an interview with Jim, the man behind Aloes. I met him at his house in North London and he was very generous in receiving me, sharing his thoughts, giving me bibliographical detail, and granting me permission to reproduce material from his archives.

Aloes Books was founded in the early 1970s by poets, artists and publishers, Allen Fisher, Richard Miller and Jim Pennington. It was part of an international network of small presses associated with various strands of modernism. Inspired by Blake’s illuminated books, young British poets took to publishing themselves and their friends, generating a flourishing movement which became known as the British Poetry Revival. With access to new and relatively cheap printing technology, Jim and his colleagues published innovative British poets like Jeff Nuttall, “champion of rebellion and experiment”; Allen Fisher, whose work has been compared to that of Ezra Pound and Charles Olson; Eric Mottram, a pioneer of American studies in the UK with close ties to the Beat Generation writers, as well as the Americans William Burroughs, Patti Smith, Ted Berrigan and others.

Pynchon’s subversive tales appealed to the young publishers – the early short stories ideal in content and length. They were also incredibly difficult to obtain, as the novelist Ian Rankin recalled:

“The few short stories Pynchon had published were hard to find in 1981. A few appeared as individual pamphlets; others had to be borrowed from Ivy League libraries in the USA.” (‘Ian Rankin and his Love of Pynchon,’ The Guardian, 18th November 2006). The pamphlets Rankin alludes to are certainly the Aloes ones; his testimony shows how important they were to students, scholars, and critics before Slow Learner. But was Clifford Mead wholly right to categorize them as piracies?

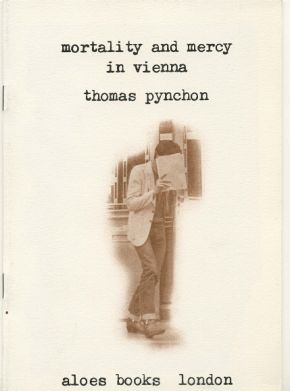

Mortality and Mercy in Vienna had first appeared in 1959 in Epoch, a Cornell University magazine, and was later republished in an Epoch anthology in 1966. Aloes published their edition in 1976 (1,000 copies), with a second printing in 1978 (2,000), and a final one in 1980 (2,000). Mead describes only the first and last, but speculates on four separate issues of the former based on the existence, colouring and number of target crosses on the cover. The first printing was carried out in a duotone red and green on smooth wrappers and in fact the variations are all down to the vagaries and register of the duotone – as long as there are one or two crosses the pamphlet is a first issue. The second has no crosses, the cover photograph now in sepia on glossy wrappers. The third printing is the same, but on rougher pulpboard wrappers.

Mortality and Mercy in Vienna had first appeared in 1959 in Epoch, a Cornell University magazine, and was later republished in an Epoch anthology in 1966. Aloes published their edition in 1976 (1,000 copies), with a second printing in 1978 (2,000), and a final one in 1980 (2,000). Mead describes only the first and last, but speculates on four separate issues of the former based on the existence, colouring and number of target crosses on the cover. The first printing was carried out in a duotone red and green on smooth wrappers and in fact the variations are all down to the vagaries and register of the duotone – as long as there are one or two crosses the pamphlet is a first issue. The second has no crosses, the cover photograph now in sepia on glossy wrappers. The third printing is the same, but on rougher pulpboard wrappers.

Although often considered the best of these early stories, it was not included in Slow Learner and the Aloes edition of this haunting story remains the only readily accessible text in book form. The cover image, with its sly suggestion that it might be the elusive Pynchon himself, is in fact a Pennington photograph of the poet Max Blagg leaving the Canal Street Post Office in New York while hiding his face with a newspaper. Aloes tried to give their pamphlets a ‘perfect’ Pynchon look, veiling the face of male characters while surrounding them with clues inviting the reader to play the decoding game. The title-page was adapted from a 1950 “Griff” pulp published by Modern Fiction Ltd. – “Griff” being the generic name for a stable of hack writers. It was adapted from Murder by Contract (1951), the story of a college-educated young man who becomes an assassin for hire – not entirely unlike Pynchon’s Irving Loon, who ends up gunning down the guests at a party.

Although often considered the best of these early stories, it was not included in Slow Learner and the Aloes edition of this haunting story remains the only readily accessible text in book form. The cover image, with its sly suggestion that it might be the elusive Pynchon himself, is in fact a Pennington photograph of the poet Max Blagg leaving the Canal Street Post Office in New York while hiding his face with a newspaper. Aloes tried to give their pamphlets a ‘perfect’ Pynchon look, veiling the face of male characters while surrounding them with clues inviting the reader to play the decoding game. The title-page was adapted from a 1950 “Griff” pulp published by Modern Fiction Ltd. – “Griff” being the generic name for a stable of hack writers. It was adapted from Murder by Contract (1951), the story of a college-educated young man who becomes an assassin for hire – not entirely unlike Pynchon’s Irving Loon, who ends up gunning down the guests at a party.

Despite being so long labelled a piracy, Aloes had ample authorization to print the story in the form of a letter from Baxter Hathaway, Pynchon’s professor at Cornell and editor of the Epoch anthology, the letter granting Aloes permission to print the work, simply asking for a credit – a credit duly given.

Low-Lands was first published in New World Writing, No. 16 (despite the internal attribution to Epoch) in 1960, with three subsequent appearances in American anthologies. The first separate edition was published by Aloes in 1978 (1,500 copies), followed by a second printing in 1980 (2,000) and a third in 1982 (1,000). The first printing has a three-colour cover on glossy wrappers, the second on rough pulp wrappers, while the third (also on pulp) lacks the price on the lower cover. The colour register can be erratic.

The design is from a photograph by Jim’s friend, the American artist Richard Mock. The inspiration came from a Mock self-portrait, with Louise Nevett colouring it up into a rubbish heap. The character on the cover is the unforgettable Pig Bodine, the “unwholesome bluejacket” who makes his first appearance in Low-Lands before appearing in V and Gravity’s Rainbow. Ian Rankin paid homage with Big Podeen, the ex-sailor who features in his first novel.

On the verso of the last page of the pamphlet we read: “Reprinted by permission of Candida Donadio & Associates, Inc.” Donadio was a powerful American literary agent, acting for Roth, Heller, Puzo, etc. Crucially, she was Pynchon’s agent from the early sixties until a letter arrived from Pynchon dated 5th January 1982: “As of this date, you are no longer authorized to represent me or my work” (Mel Gussow, ‘Pynchon’s Letters Nudge his Mask’, New York Times, 4th March 1998).

Five years earlier, Aloes had received a letter from Candida Donadio & Associates: “We are happy to inform you that permission has been granted to publish Low-Lands in a soft cover text. The permission to reprint Mr. Pynchon’s story is $75.00. Please fill out and sign the enclosed permission forms, returning one copy to us … To complete our collection of publications of Mr. Pynchon’s work, if at all possible, please send us six copies of Mortality and Mercy in Vienna.” The second Aloes pamphlet was no more a piracy than the first.

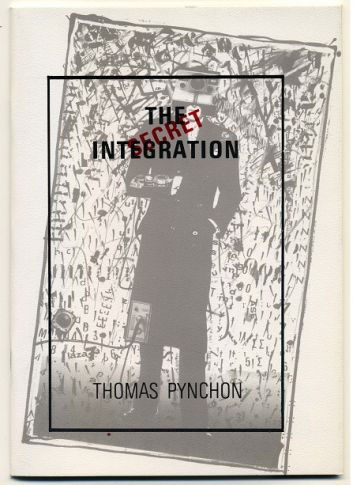

The Secret Integration first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, 19th-26th December 1964, and was reprinted in an Evening Post anthology in 1965. The first separate edition was published by Aloes in 1980 with a stated print-run of 2,500, although there may have been nearer 3,000 copies. There were two further printings in 1982-1983 (1,500 copies in all). The first printing notes the print-run and the cover is on smooth glossy card; the second printing omits the print-run detail and the cover is a rough pebble-finish; the third printing is the same but on less glossy card. The first printing is 1mm larger all around.

The Secret Integration first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, 19th-26th December 1964, and was reprinted in an Evening Post anthology in 1965. The first separate edition was published by Aloes in 1980 with a stated print-run of 2,500, although there may have been nearer 3,000 copies. There were two further printings in 1982-1983 (1,500 copies in all). The first printing notes the print-run and the cover is on smooth glossy card; the second printing omits the print-run detail and the cover is a rough pebble-finish; the third printing is the same but on less glossy card. The first printing is 1mm larger all around.

The cover design by Jake Tilson portrays a figure – half-man, half-machine – in an elegant frock-coat with a Polaroid camera for a head on a background of mathematical symbols. The story is about racial integration, but also uses ideas of mathematical integration, while the cover suggests integration between humans and machines.

Jim Pennington had approached Donadio & Associates again, seeking permission to publish The Secret Integration and Entropy. His initial letter explained: “It is our intention to produce these two important works in a small edition of 3,000 copies, bound as a pamphlet in the same way as our previous editions of Mortality and Mercy in Vienna and Low-Lands. The purpose of the edition is to make available to students and those interested in the author’s work texts that are otherwise very inaccessible. You may not be aware that The Secret Integration is not even held at the British Museum [sic] Newspaper Library since they are missing that particular year of the Saturday Evening Post. The only English edition of Entropy is contained in a relatively obscure science fiction magazine [New Worlds, February 1969] that has ceased publication also. Our cover price is to be £1.00 in UK and $5.00 in the USA. We expect to make a small profit should we be able to publish and this will go toward financing our loss-making publications in the field of experimental poetry”.Having received no response, with permission neither given nor denied despite several applications, Aloes proceeded to publish The Secret Integration. This was followed in 1982 by an edition, not of Entropy, which had now been published in England by Tristero, but of The Small Rain.

Version 1.0.0

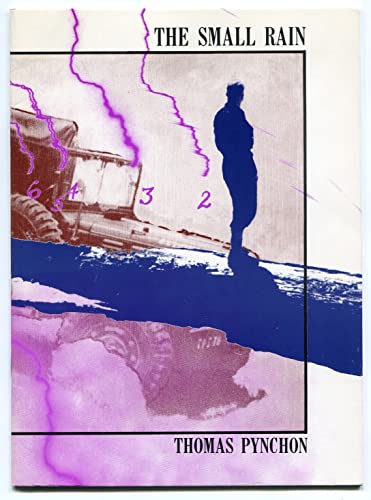

In the story, Private Nathan “Lardass” Levine is part of an army rescue operation in a post-hurricane situation in a small southern town. The Aloes cover, designed by Robert Carter, depicts a man contemplating a desolate landscape with a military vehicle as his only companion. It was to be the last the Aloes Pynchons. On 7th September 1983, the Aloes distributor in the United States (Bookslingers) received a letter from Pynchon’s new agent (and future wife), Melanie Jackson:

“As we discussed on the phone yesterday, Thomas Pynchon is extremely upset about the illegal distribution of pirate editions of his short stories. Anything you can do to prevent further distribution of these Aloes editions would be much appreciated by all concerned”.

Was the publication of Slow Learner provoked by the Aloes pamphlets? The picture may have been distorted by the appearance at around this time of two further UK Pynchon pamphlets, Entropy published by Tristero and A Journey into the Mind of Watts published by Mouldwarp. As Jim Pennington pointed out, “Neither of these pamphlets has any connection with Aloes and a quick look at their style of production will bear this out” – but Aloes may have suffered as a result. Pynchon may have changed his mind about Aloes and their evocative artwork, or the idea of funding avant-garde poets, or may never have sanctioned his agent’s original acquiescence, but there was certainly little sympathy now – and no mention at all of the previous agreements. In a dignified response, Jim explained: “We have always endeavoured to give our Pynchon books, indeed all our books, the best production our budgets will stretch to. The success of the Pynchon titles has enabled us to give increasingly sophisticated design to each subsequent title and I had imagined that this ulterior motive, applied as it has been to our lesser known authors, was one of the reasons we were given permission in the first place”.

The last letter on file, dated 1st March 1984, is from Deborah Rogers, London literary agent:

“After much discussion with Mr. Pynchon, I understand he is prepared not to pursue this if we can reach some satisfactory arrangement.” If so, “I can suggest to Mr. Pynchon that he considers the possibility of allowing you to sell off your remaining stock, subject to a formal agreement restricting you to the sale of those pamphlets only.” This last letter, written in a softer tone, records how the position was eventually resolved.

Unlike Oedipa, who started on her strange trail of detection with a pirated edition, it seemed that, contrary to general belief, I had started my quest with entirely legitimate editions of Mortality and Mercy in Vienna and Low-Lands. The other two stories were published with the knowledge and at least tacit approval of Pynchon’s original agent, who had made no objection. There was also a “satisfactory arrangement” with Pynchon’s representatives. The “piracies” turn out not to be so and the “pirate” to have been a legitimate poetry press making significant contributions to the literary landscape of both Britain and the United States – not least in probably provoking Thomas Pynchon to reveal more about himself than he ever has before or since. As for Pynchon himself, I hope one day he will reveal more about the wonderfully strange and still uncollected Mortality and Mercy in Vienna.

Leave a Reply