by Tore Rye Andersen

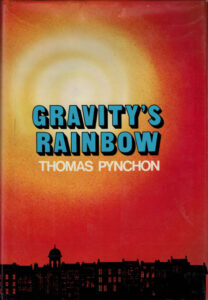

The Pynchon Wiki features a great little article by Linda Getter on her husband Marc Getter, the artist behind the striking dust-jacket of the first edition of Gravity’s Rainbow. According to Linda, Marc “loved the idea of a single image being responsible for communicating the essence of a book.” This is a lot to ask of a cover illustration, especially when the book it adorns is as complex as Gravity’s Rainbow, where rockets, dodoes, and pigs intermingle, and where excruciatingly beautiful landscape descriptions and vulgar sex scenes appear side by side with cartoonish tales of the future and pointed political satire. Even though it can be discussed whether Getter’s image communicates the essence of Pynchon’s masterpiece, the cover is certainly iconic. The vibrant colors (which are notoriously prone to fading) make the jacket pop, and the three-dimensional blue letters of the title and the sharp black silhouette of the London townhouses form an arresting contrast to the soft, airbrushed orange and yellow sky.[1]On the 1975 first edition of the French translation of the novel (incongruously titled Rainbow), the anonymous row of townhouses has been replaced with a more recognizable skyline that includes St. … Continue readingI recently published the monograph Planetary Pynchon: History, Modernity, and the Anthropocene (Cambridge University Press, 2023). The book is in many ways a life’s work, a summation of thirty years of deep fascination with and research on Pynchon’s work. As part of this fascination, I have written quite a few articles throughout the years on the paratexts of Pynchon’s novels, including analyses of the covers of V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, and Inherent Vice. While the paratextual dimension is not central to my new book, my interest in book design made the task of choosing just the right cover image for my book a daunting one.

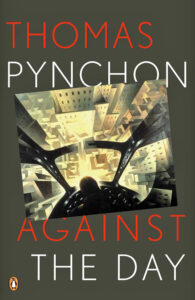

Briefly told, my book argues that Pynchon’s three largest novels — Gravity’s Rainbow, Mason & Dixon, and Against the Day — can profitably be read as a trilogy, or one large megatext, which presents a coherent world-historical account of how the emergence and global spread of European modernity and resultant phenomena such as industrialization, capitalism, and colonialism have threatened and often eradicated alternative worldviews, peoples, and other lifeforms, all with disastrous consequences for the planet. In other words, Pynchon’s global novels show how the rise of modernity led to the current age of the Anthropocene.

The influential concept of the Anthropocene was introduced in 2000 by Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, who argued that the activities of humankind have now left such an indelible impact on the planet that we have entered a new geological epoch. While discussions of the relation between literature and the Anthropocene usually focus on fiction that was written after the concept was introduced, my book argues that Gravity’s Rainbow very much anticipates current ideas about the Anthropocene and the related notion of planetarity, and that the other two global novels extend and refine Pynchon’s arguments. The global trilogy is accordingly as relevant as ever.

These are grand — some would probably say quixotic — topics, so how (with Marc Getter) should they be communicated in a single cover image? I knew in advance that I would like to pay homage to one or more of the many Pynchon covers I have written about, and while this ambition did not exactly point in any clear direction, it did limit the field somewhat. My first idea was a painting by the Italian Futurist Tullio Crali. His painting Nose-diving on the City (1939) graces the US paperback edition of Against the Day and even seems to be embedded in the text of the novel itself, in a passage that describes Kit Traverse and his friend Renzo nosediving on Torino in a bomber plane, and which is simultaneously a fitting description of humanity’s headlong plunge into modernity:At some point I had stumbled on a painting from the same series, Before the Parachute Opens (1939) — a striking image which, like Pynchon’s novels, expressed many things at once. The spread arms of the parachutist that seem to dissolve into the surroundings reminded me of an angel, even while the image also connoted the harsh realities of war. Moreover, the plunge of the parachutist spoke of our blind trust in technology, just as it hinted at the scary possibility that the parachute would not open this time, that it was too late. Finally, the painting provided an aerial view of cultivated and subdivided fields and thus of our utilitarian relation to nature — a fitting illustration of the Anthropocene. While Cambridge University Press’s guide to choosing the right cover image for your book sensibly warns that an image that tries “to portray the subtlety of a particular argument will only confuse the reader,” I was quite fond of Crali’s painting and attempted to contact the estate to secure the rights to reproduce it. However, after repeated attempts to get in touch with the heirs yielded no results, I had to resort to my second idea, and retrospectively I am glad that I was forced to do so.They were soon going so fast that something happened to time, and maybe they’d slipped for a short interval into the Future, the Future known to Italian Futurists, with events superimposed on one another, and geometry straining irrationally away in all directions including a couple of extra dimensions as they continued hellward, a Hell that could never contain Kit’s abducted young wife, to which he would never go to rescue her, which was actually Hell-of-the-future, taken on into its functional equations, stripped and fire-blasted of everything emotional or accidental…. (AtD 1070)

Even though it features a row of London townhouses, to my mind Marc Getter’s glowing dust-jacket for Gravity’s Rainbow also recalls a memorable scene in the novel where a drunken Slothrop staggers out of Casino Hermann Goering and sees a spectacular sunset:

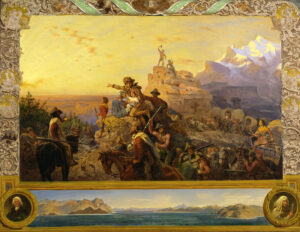

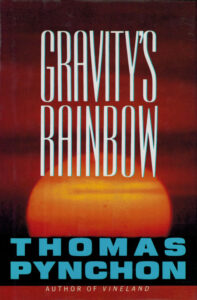

In this fabulous passage, Pynchon first paints a memorable picture of a gorgeous, almost anachronistic natural phenomenon, but the description soon morphs into a gloomy reflection that the purity and beauty of this sunset will soon be (or has indeed already been) spoiled by the westward progress of Empire — a reference to George Berkeley’s verse line “Westward the Course of Empire takes its Way,” which has also provided the title for a painting from 1861 by Emanuel Leutze (prominently displayed in the US Capitol Building). The ambiguous gist of Pynchon’s description is in many ways a nice encapsulation of the central theme in my book, which traces the global trilogy’s progressive depiction of how unbounded nature is gradually colonized by humankind and its technological prostheses (the measuring of the Mason-Dixon Line in Mason & Dixon and the growth of the railroad in Against the Day are both instances of this process). I find the same ambiguity in Marc Getter’s cover image, where we can not be absolutely certain that the sun is actually the sun: Perhaps it is really a rocket, incoming mail bearing very bad news indeed. Which do you want it to be? The second hardcover edition of Gravity’s Rainbow (1991) features a similar uncertainty. It may depict the sun, but the sun seems to be oddly flattened, so could it represent something more ominous? This eerie ambiguity gave me something to work with, and after trawling through the vast online archive of Getty Images, I found just what I was looking for. At a first glance, the cover photo seems to depict a spectacular sunset of the kind witnessed by Slothrop at the Riviera, a purity begging to be polluted. Upon closer inspection, however, the sun appears to have ragged edges that are not just an effect of the surrounding clouds. As it turns out, the sunset is not really a sunset, after all, but a nuclear detonation.[2]More specifically, the photo depicts the atomic bomb code-named “Apache,” which was detonated at the Enewetak Atoll during Operation Redwing in 1956. As readers of Gravity’s Rainbow know full well, the specter of the atomic bomb hovers over the end of that novel: Slothrop learns of the atomic bomb being dropped on Hiroshima through a torn newspaper photo (GR 693), and an elaborate dance routine in Cuxhaven takes place at the exact moment when the Hiroshima bomb detonated, as Steven Weisenburger has shown, just as its choreography mimics the explosion itself (GR 593-94). Moreover, a flash-forward to around 1970 tells of the Los Angeles Basin being filled with the all-encompassing sound of a siren that echoes the screaming that comes across the sky in the novel’s opening line, and which surely announces World War Three (GR 757); and on the last page, readers are left in a dark cinema with what appears to be a nuclear missile hanging the last delta-t above their heads (GR 760).“Holy shit.” This is the kind of sunset you hardly see any more, a 19th-century wilderness sunset, a few of which got set down, approximated, on canvas, landscapes of the American West by artists nobody ever heard of, where the land was still free and the eye innocent, and the presence of the Creator much more direct. Here it thunders now over the Mediterranean, high and lonely, this anachronism in primal red, in yellow purer than can be found anywhere today, a purity begging to be polluted… of course Empire took its way westward, what other way was there but into those virgin sunsets to penetrate and to foul? — (GR 214)

The Bomb thus features prominently in the last sections of Gravity’s Rainbow. At the same time, and of particular relevance to my book, the first nuclear detonations are often regarded as the true beginning of the Anthropocene, since the fallout from those explosions have left lasting traces in the geological layers of Earth.[3]Another often proposed starting date is the latter part of the eighteenth century, where James Watt invented the steam engine and industrialization took off in earnest. This period is of course … Continue reading The atomic bomb is a violent culmination of technological modernity, where humankind in Prometheus-like fashion seized godlike powers and for the first time in history obtained the ability to destroy the planet.

The photo of the sunlike nuclear detonation on the cover of Planetary Pynchon is thus a clear homage to Marc Getter’s iconic cover for Gravity’s Rainbow, my favorite novel in the global trilogy.[4]As Paolo Simonetti has kindly pointed out, the image also evokes the original poster for Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), another story about war and imperialism. The photo connotes a beautiful sunset like the one admired by Slothrop, and at the same time, in a sneaky détournement, it embodies the ultimate pollution of this sunset. Finally, it provides — whether we see the glowing fireball as the sun or as the Bomb — references to our rapidly heating planet, one of the clearest manifestations of the Anthropocene and a direct consequence of our ruthless exploitation of natural resources such as fossil fuel. Just like Pynchon’s global trilogy, the image thus reminds us — as if we needed a reminder — that “[l]iving inside the System is like riding across the country in a bus driven by a maniac bent on suicide…” (GR 412).

It is perhaps naïve to expect that a single image can communicate the essence of a whole book, and many of the arguments in my book have nothing whatsoever to do with its cover image. Still, I am very pleased with how the cover turned out, and I hope that Marc Getter would have approved.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | On the 1975 first edition of the French translation of the novel (incongruously titled Rainbow), the anonymous row of townhouses has been replaced with a more recognizable skyline that includes St. Paul’s Cathedral and Tower Bridge. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | More specifically, the photo depicts the atomic bomb code-named “Apache,” which was detonated at the Enewetak Atoll during Operation Redwing in 1956. |

| ↑3 | Another often proposed starting date is the latter part of the eighteenth century, where James Watt invented the steam engine and industrialization took off in earnest. This period is of course concurrent with Mason & Dixon, and Pynchon’s global trilogy thus depicts the historical span between the two most frequently proposed starting dates of the Anthropocene. |

| ↑4 | As Paolo Simonetti has kindly pointed out, the image also evokes the original poster for Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), another story about war and imperialism. |

Your book sounds fascinating, but when I checked the price on Amazon I dismissed any thought of being able to obtain it.