NOTE: Inside parenthetical citations: [P] = material from Pynchon’s draft; [S] = passage from Kirkpatrick Sale’s draft

“Minstrel Island” by Thomas Pynchon & Kirkpatrick Sale

“Minstrel Island” is an unpublished, unfinished musical (it’s also been referred to as a “science fiction musical” and “operetta”) written by Thomas Pynchon and his friend John Kirkpatrick Sale while they were attending Cornell University. The materials — one folder of handwritten and typed notes, outlines, and draft fragments from sometime in the spring of 1958 — are in the collection of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin.

The incomplete state of “Minstrel Island” allows us to observe something about the process that Thomas Pynchon and Kirkpatrick Sale followed as they tried to turn an idea into a piece of writing. The following note sets out to demonstrate, as much as possible, the order in which the material was completed, something that allows us to discern at least one of the differences between Pynchon’s and Sale’s artistic sensibility.

The available material consists of:

- Pynchon’s handwritten draft of Act I, scenes 1 and 2, and handwritten prefatory material that sets the scene for the action of the play;

- Sale’s typed extensive outlines of Act I, Scene 3, Act II, Scenes 2 and 3, and Act III, Scenes 1;

- Sale’s typed draft of the scenes that Pynchon also drafted, with typed prefatory material;

- Pynchon’s handwritten skeletal outlines of all the scenes up to Act III, scene 3, that is, the play’s end; and

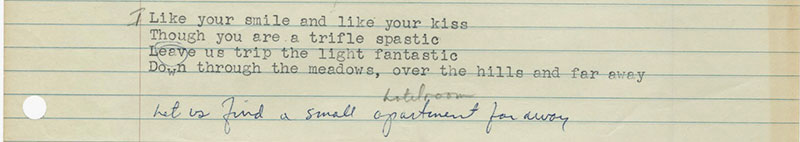

- drafts of songs, most of them handwritten, though not exclusively in Pynchon’s hand.

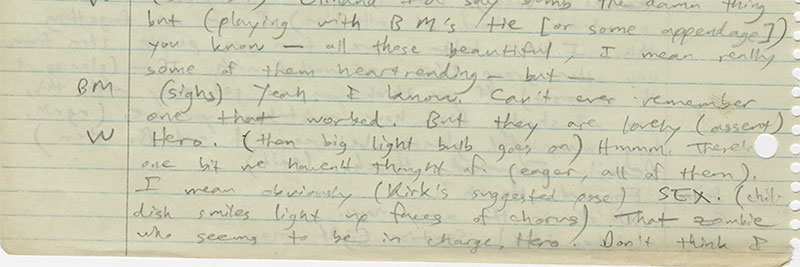

Elements of this material strongly suggests that Sale’s outlines and drafts were typed before Pynchon drafted his first two scenes, but after Sale and Pynchon discussed the content of the play together and perhaps after Pynchon jotted down his own outlines, which contain only a few fragmented lines for each scene. That Sale did his work before Pynchon drafted his version of Act I, scenes 1 and 2, as well as the probability that Pynchon had Sale’s material in hand when writing those scenes, is revealed by Pynchon’s including such references to the typed draft as the parenthetical note in his Act I, scene 1, “Kirk’s suggested pose,” which is “She throws her head back, sticks her breasts out, spreads her feet” ([S] Act I, scene 1) and by the presence of near verbatim lines in both versions.

Still, Sale must have brought to his work some notion of the content to which he was setting out to give form, something suggested by similarities between his drafts and outlines and Pynchon’s work, as well as by differences between things in his outlines and things in his drafted scenes.

The Use of Placeholders

The use of placeholder names is even revealing. Pynchon usually skips naming the main characters in his outlines; Broad and Hero are mostly referred to as “girl” and “boy,” though the names Hero, Prostitute, Sailmaker, Jazzman, Dud Bomber, Tube Tester, and Johnny Badass — who is also called IBM Hero in the notes to Act I, scene 3 — are scattered throughout. Pynchon even mentions a jazz group, the plan for which indicates that Sale’s having more than one Jazzman in his version of Scene 1 makes more sense than Pynchon’s having only one.

Sale, in his outlines, uses placeholders that are either the same or similar to the ones appearing in Pynchon’s, but Sale attempts to establish realistic names in his drafted scenes, calling Broad — a placeholder first appearing in his outline — Ivy and Johnny Badass, Mr. x, a placeholder as well but one that acknowledges that the “Vice President in charge of the N.Y. area for IBM” ([P] Act I, scene 2) would have a formal sounding name. Pynchon seems to have been unhappy with those choices, for he uses Broad and Johnny Badass in his drafts.

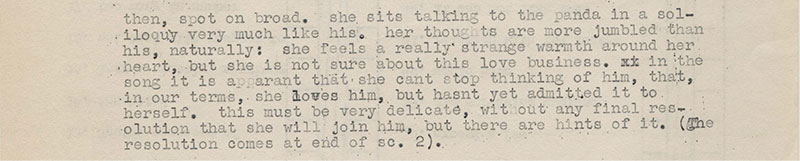

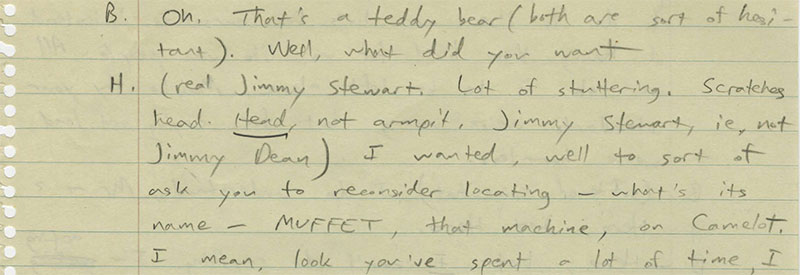

The most suggestive element of the differences is that the “teddy bear” Hero gives Broad in Pynchon’s Act I, scene 2, is a “panda bear” in Pynchon’s outline as well as in Sale’s outline of Act III, scene 1. The only reference to a bear in Sale’s version of Act I, scene 2, is Pynchon’s handwritten text above stage directions that follow a song sung by Hero that Sale does not include, even though the carnival booth is, according to the prefatory material that sets the scene, “perhaps a knock-the-cat-off-win-a-teddy-bear booth,” which is what appears in Pynchon’s version of the scene. Pynchon’s text on Sale’s version reads, “goes behind booth, picks up Teddy bear, gently gives it to the girl, then,” words that are meant to be placed in between the typed text “Hero” and “bends and kisses girl” and that correspond, except for the type of bear, to Pynchon’s outline. Pynchon’s full description of scene 2 is

2) Same setting

Boy + girl meet – fall in love

Girl of computer – feeds cards

boy sings love song after they talk – he gives her panda.

She’s confused – he goes off – she ponders w/ machine.

Sale could have forgotten the bear when typing up his drafts. The bear’s appearance in the outline of Sale’s Act III, scene 1, demonstrates that he knew Hero was to give one to Broad, and while Hero could give the panda bear to Broad in Sale’s Act II, scene 1, the description of which is lost, that is unlikely. In Pynchon’s outline of Act II, scene 1, Broad is alone in her room, and it is probable that Pynchon and Sale had worked out the content of each scene before drafting the outlines, given that all the scenes that we have from the two versions of the outlines take place in the same settings.

The only problem with accepting that theory is that the stage direction in Pynchon’s version of Act I, scene 2, which appears just after Broad mentions the bear—that is, when she first arrives on the scene and asks Hero what he wants—reads, “real Jimmy Stewart. Lot of stuttering. Scratches head. Head, not armpit. Jimmy Stewart, ie, not Jimmy Dean.” Explaining the distinction between the two Jimmies could mean that Sale referenced the wrong actor in text that is lost and Pynchon is correcting him. Of course, Sale, if he wasn’t as knowledgeable about movie stars as Pynchon, could have confused the two actors in a conversation about the scene, leading Pynchon to emphasize the difference here, or Pynchon could simply be indicating that he has changed his mind about what actor to reference. Hero, after all, “scratches armpit” after Broad tells him that his laziness is the cause of his unemployment, not the IBMers’ rendering his profession unnecessary.

Why Pynchon changed the “panda bear” to a “Teddy Bear,” a change that Sale’s description of the booth may have led him to consider, seems more straightforward and reveals something about how his approach to the material differs from Sale’s. Pynchon was likely aware that the Teddy Bear was named after Theodore Roosevelt. A Pynchon-Roosevelt connection was important enough to his father to deserve discussion in Pynchon, Sr.’s obituary. “Ethel Roosevelt, T.R.’s daughter, was [Pynchon, Sr.’s] Sunday school teacher. The Roosevelts and Pynchons were very close,” John Gable, executive director of the Theodore Roosevelt Association, told Justin Martin for New York Newsday. “He [Pynchon, Sr.] told me he remembered going to church on Sundays and saluting Mr. Roosevelt at his pew, and Mr. Roosevelt always saluted him back” (“Ex-Oyster Bay Chief Who Knew T.R. Dies,” Newsday [Nassau and Suffolk ed.], 23 July 1995, A10). Roosevelt was responsible for expanding the number of National Parks and came to be known as the “conservation president” for the work he did to preserve natural lands from the impact of modern life, which is sort of how the minstrels want the IBMers to treat the island, that is, as a place apart in which elements of the past that modern living will destroy is preserved, something evinced by Hero’s telling Broad,

All we want is someplace where every time we turn around we don’t see that idiot damn machine staring at us. We’re not hurting you people. We don’t start revolutions, we don’t preach any inflammatory doctrines. All we ask is to be left alone. Maybe by your standards we’re wrong but for crying out loud, we’re harmless. ([P] Act I, scene 2)

The Teddy bear is an apt symbol of Hero’s hope. The change from Panda to Teddy Bear thus demonstrates how Pynchon looks to integrate the parts more meaningfully into the whole. Other differences between the two versions of the drafted scenes back up such an assessment. Sale, for instance, made the carnival booth the setting for the second scene but apparently did so indifferently or for a practical reason—to avoid having to bring new props on stage, since the booth is present in scene 1. Despite choosing the setting, Sale doesn’t do anything with it in his version of the scene, which could be changed without significant changes to the action and dialogue. Pynchon, on the other hand, integrates the scenery into the dialogue and action, chiefly by building a story around the Teddy Bear, and significant changes would need to be made if the scene were moved, say, to the front of the Ferris Wheel.

Similarly, the computer that the IBMers are planning to build on the island becomes in Pynchon’s version, “the Musical Unidirectional Force Field Equipped Tabulator. . . . Abbreviated MUFFET,” which, of course, alludes to the nursery rhyme in which the proper Miss Muffet is thrown into confusion by the appearance of a spider, a creature who does not acknowledge the world of propriety. The name of the computer alludes to the action of the entire play, the disturbing of the social propriety of the IBM society by the minstrels, symbolically the spider, albeit one whose powers are less obvious than that of the nursery rhyme character. MUFFET, after all, is unlikely to be gotten off the island. Indeed, if this MUFFET is a precursor to the MUFFET in “Entropy,” the “Multi-unit factorial field electronic tabulator,” (90) that has Miriam, the apparently soon-to-be-ex-wife of Saul, “bugged at the idea of computers acting like people,” such machines serve to drive away the bugs, bugs whose presence raises questions about the machines’ problematic power.

That is not to say that Sale is indifferent to the symbolic significance of the play’s elements. The name “Ivy” is itself subtly symbolic. Johnny Badass is described as “pompous, very ivy dressed” in the description of Act I, scene 3, suggesting that, for Sale, Ivy is short for Ivy League, making such universities, symbolically speaking, secretaries to the powers that be in the culture at large. Sale, however, seems more interested in social commentary than anything else, that is, in the message the play has for the audience, not in how the parts work together. Pynchon is concerned with how the elements contribute to the play’s symbolic network as well as meaning, to create which he plays with allusions. The references to pop-cultural figures, Jimmy Stewart in Act I, scene ii, Frank Sinatra in Act III, scene 1, are meant to provide visual clues to help the audience better understand the scenes. The audience should get that Hero’s movements mimic pop-cultural figures, drawing significance from the common late-fifties reading of their characteristic poses.

Sale, by contrast, draws on cultural types, for example, the “mad ave fraternity boy” (Act I, scene 3) or “the modern business woman” (Act I, scene 1), to develop a realistic world that should be immediately understood so that the audience can see its faults reflected in the 1998 dystopia. (I’m assuming each of the outlines contains material introduced by the other contributor, so Sale includes the Sinatra reference, which Pynchon’s known predilection for drawing on pop culture suggests he would have used, in the third act, while Pynchon jots down the phrase “mad ave boy” in his outline to Act I, scene 3, the description of which in Sale’s outline resembles Sale’s description of Broad as the “epitome of the modern business woman” at the beginning of Act I, scene 1.) The panda, just as the scenery in Act I, scene 2, serves as nothing more than a prop in such an approach, so Sale leaves the bear out when drafting the scene in which Hero gives it to Broad and leaves it as a panda in Act III, despite his writing that the carnival booth could be a knock-the-cat-off-win-a-teddy-bear booth.

***

Albert Rolls is the editor-in-chief at AMS Press, Inc., and an independent researcher, as he never abandoned the reading practices he developed while completing his graduate degrees. He has published a number of articles on Pynchon in Orbit.

[…] according to Wired — author Kirkpatrick Sale. “Sale while a student in the 1950s co-wrote a musical with Thomas Pynchon about escaping a dystopian America ruled by IBM,” remembers Slashdot reader […]