Epic Agent: The Great Candida Donadio

by Karen Hudes

This profile first appeared in Tin House (Volume 6, Number 4), Summer 2005.

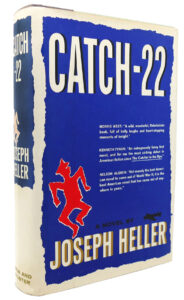

Candida Donadio was the most powerful, gifted, and beloved literary agent of her generation. She was the sixties maverick who discovered Joseph Heller and Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth and William Gaddis. Her list of clients glittered with such writers as Mario Puzo, Robert Stone, and John Cheever.

“She had an unerring instinct for offbeat talent,” says Robert Gottlieb, the former editor in chief of Alfred A. Knopf and The New Yorker, and the editor of Catch-22 — the book that made the careers of Heller, Donadio, and himself.

This luminary of the publishing world possessed not only an eye for genius, but also magnetism and warmth. “If she acknowledged your existence, it was like you were knighted,” says Juris Jurjevics, the publisher of Soho Press who was married to one of Donadio’s clients, the late Laurie Colwin.

Donadio was born on October 22, 1929 — a date that may or may not have factored into the naming of Catch-22, depending on whom you believe. Her lovely, Pynchonesque name (pronounced “CAN-dida,” meaning white or pure) made news beyond the literary scene in 1998 when it appeared in a New York Times article regarding a donation to the Pierpont Morgan Library — a collection of more than 120 letters from Pynchon to Donadio, which she had sold to a private collector in 1984. Pynchon’s lawyer took immediate action, ensuring that the letters not be made public until the author’s death.

Donadio’s sale of the letters came in the aftermath of a messy professional separation between her and Pynchon, and may speak to the volatility of her character.

“People tell a lot of contradictory stories about Candida, and they’re all true,” says Neil Olson, who began as her assistant in 1987 and is now the head of the agency Donadio & Olson. “I think her true nature really was a shy, self-doubting, very smart, very sharp person who was capable of having these operatic explosions into this figure who carried on and pulled her hair and shouted other people down… But these explosions were very seldom directed at anybody, they were just going on inside of her.”

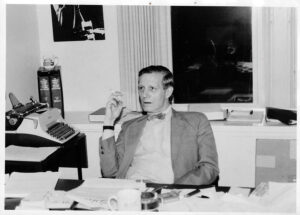

Donadio was short and round, wearing her black hair in a severe bun. Most distinctive were her beautiful, dark, and deeply expressive brown eyes.

“She looked like a creature from a Roman fresco,” says Robert Stone, her client for more than thirty years.

By numerous accounts, Donadio could be frank and forthright, as well as an embellisher of tales. She had a rich, low voice and bawdy sense of humor, flavoring her conversation with both Yiddish slang and Sicilian hand gestures. Yet she was intensely private and, like Pynchon, disliked being photographed or interviewed.

Like many of her contemporaries, Donadio was fond of martinis at lunch and scotch after work. She was also a heavy smoker. While deliberating over business, she’d take a few drags off one cigarette before stubbing it out and lighting the next. She could often be seen at the Italian Pavilion, now Michael’s, where she held a regular table.

When Olson arrived, the agency was housed in a brownstone facing the back of the Chelsea Hotel. “You could hear the opera singers, hear people screaming, throwing glass,” he says. There were two cats and a working fireplace, and electricity that always went out. Donadio would toss notes to him from her mezzanine office, letting them waft down into his hands. “Like Juliet,” he says.

“She acted spectacular, but she was modest,” says Corlies “Cork” Smith, Pynchon’s first editor and a longtime friend of Donadio. He adds, “She had more synonyms for excrement than anyone you’d ever run across.”Among her many colorful expressions: “I thought my navel would unscrew and my ass would fall off.” So remembers Harriet Wasserman, who was a secretary at Herb Jaffe Associates in 1958 when she befriended Donadio, and who later worked as her assistant. Wasserman went on to become a high-powered agent herself, representing Saul Bellow, Reynolds Price, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala.

She recalls her mentor pronouncing her name, “Candida Donadio, a pure gift of God.”

Candida grew up in Brooklyn, the daughter of Italian immigrants. Her father, whose side of the family came by way of Brazil, worked for the post office. She had two siblings, Louis and Frances, from whom she grew estranged by adulthood. Her formal education may have included a few classes after high school, but for the most part, she was self-taught.

It’s not clear when her ambition to become an agent took root. She began her unlikely career in the early fifties as a secretary at the agency of McIntosh & Otis, and soon grew involved with handling authors and building her own list. In 1953, Donadio received the first rough chapters of what was then called “Catch-18.”

Olson says, “She saw something in that wild and crazy, surrealistic, bent-headed humor.” When she sent out the manuscript, he says, she kept hearing the same replies over and over again — that “this is not writing, this is foolishness. While he was alive Heller tried to suppress that his genius was not recognized instantly, but it was after many, many submissions that Bob Gottlieb … that again is one of those grand old figures, but he was a kid then, too. They were all kids.”Heller, who dedicated the 1994 edition of Catch-22 to Donadio and Gottlieb, recounts in the preface sending out his early manuscript to McIntosh: “The agents were not impressed, but a young assistant there, Ms. Candida Donadio, was, and she secured permission to submit that chapter to a few publications that regularly published excerpts from ‘novels in progress.'”

It took until 1957, when Heller was thirty-four, to sell the novel, by which time the unfinished manuscript still comprised only eighty or ninety pages. Heller writes, “[Donadio] was drawn to a new young editor she knew of at Simon & Schuster, one she thought might prove more receptive to innovation than most. His name was Robert Gottlieb, and she was right.”

“It was basically at the beginning of what we used to call ‘black humor,'” says Gottlieb, who was twenty-six at the time. “I thought it was very brilliant and we gave him a very modest contract.”

On top of all the significant obstacles to its success — an unknown author, an unfinished novel, an oddball style — Gottlieb, Heller, and Donadio had to confront another hurdle. The novel Mila 18 by Leon Uris, his follow-up to the best-selling Exodus, was scheduled to come out that same season in 1961. “You couldn’t have an unknown book with the same number,” Gottlieb says. “So we were all in despair.”

Candida’s New York Times obituary notes, “Ms. Donadio said the number 22 was chosen as a substitute because Oct. 22 was her birthday.”

“Absolutely untrue,” says Gottlieb. “I remember it totally, because it was in the middle of the night … I remember Joe came up with some number and I said, ‘No, it’s not funny,’ which is ridiculous, because no number is intrinsically funny … And then I was lying in bed worrying about it one night, and I suddenly had this revelation. And I called him the next morning and said, ‘I’ve got the perfect number. ‘Twenty-two, it’s funnier than eighteen.’ I remember those words being spoken … He said, ‘Yes, it’s great, it’s great.’ And we called Candida and told her.”

“It was funny, it was so ridiculous. We were kids, we were so in love with the book and so desperate that it be done right. Every single decision was like a major crisis … It was wonderful for Joe, because I’ve never known a writer who took a more innocent, and marvelous, happy, wholesome joy in his success. He really appreciated it, it had been a long time coming. And he just loved it. He loved being the author of Catch-22.”

So what of the “22” from Donadio’s birthday?

“That’s a typical Candida invention,” Gottlieb says.

Suggestions of Donadio’s “inventive” streak from other sources would support Gottlieb’s take. Yet his brittle assessment speaks less of a dispute over the “22” than of the problems that ultimately wedged him and Donadio apart.

Beginning with their first success, Donadio and Gottlieb’s camaraderie grew over a period of many years, during which time she gave him the first look at most manuscripts (a cause of some resentment among other editors). She sold him fiction by Bruce Jay Friedman, Wallace Markfield, and John Cheever, as well as The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford, which became a number-one Times bestseller. Donadio was the friend he talked to when he was considering leaving Simon & Schuster, and she placed the call that got him hired at Random House the next day.At that time, Donadio and Gottlieb were so dominant an agent-editor team that Esquire anointed them “the red hot center” of the New York publishing world.

“We were of an age, and we had the same interests and the same tastes to a large extent,” Gottlieb says. “It was a real friendship.” Donadio lived down the block from him, on Fifty-third Street and Second Avenue, and would “pad over in her sneakers and babysit.” He threw the dinner party at his house for her first wedding in 1965.

Yet, Gottlieb says, “There was a very big dark side. She was a hidden person.”

Along with her two fraught marriages, he was aware of other pressures and disappointments she suffered. “She was very driven by a fear of failure,” he says. “I think she felt she wasn’t attractive. She loved children, she never had any, that was a problem. She did more drinking than she should have done — this was later. When she was young she was just great. When that first flush of success receded a little … People found her a little tricky. And she could be tricky, because she did not always say exactly what was so. And that was the cause of our very serious quarrel.”

Knopf senior editor, vice president, and associate publisher Victoria Wilson, who was hired by Gottlieb, became acquainted with Donadio in the eighties, publishing novels by her clients Cathleen Schine, Walter Abish, and Laurie Colwin. “There was something that was unbelievably beautiful about her, and sexy. And she was very funny,” Wilson says. “She was a good negotiator. She understood what was possible and what wasn’t possible. For those writers where the books could withstand huge advances, she got them.”

“She would sort of start whimpering at you if you gave her a low offer for a book. She would be operatic, but she would start with the snorkeling and snorfling. It was charming, I mean it was very disarming … She could be joking and stamp her heels and say ‘caca,’ which is what she used to say all the time. ‘That’s caca.’ But at heart and very deep down she was totally elegant … I loved working with her because she had great taste.”

Edward Hibbert, a partner at Donadio & Olson, played the recurring role of restaurant critic Gil Chesterton on Frasier. He has a British accent and a great booming voice, which he lowers to a near drone to imitate Candida negotiating by telephone. “‘Here’s what I think we have to do,” he says. “And you’d think, this is brilliant. It wasn’t hyper, like ‘I need this for my client!’ It was done in a very conversationally chatty, menschy sort of way. But the effects would be extraordinary. You’d realize at the end of it, in the most non-agent-like way she got everything she wanted.”

One day in 1961, while working at the agency Russell & Volkening, Harriet Wasserman remembers waiting for Donadio while she was finishing a phone call. The editor on the line told her he was “sending over a writer who’s either insane or a genius.” In came a guy with a walrus mustache, a fedora, and a trench coat, to drop off his manuscript. It was Thomas Pynchon.

“Candida deemed him a genius,” Wasserman says. “It’s intuitive — it’s kind of a gift to recognize. He could have been neither.”

Donadio called up Cork Smith, then an editor at the J.B. Lippincott publishing house in Philadelphia, who had published Pynchon’s first paid story, “Low-lands,” in the journal New World Writing in 1960, when the writer was twenty-two. She offered Smith first dibs at a book contract — thereby sealing the agent and editor’s lifelong friendship.

The author was hardly an easy sell for Donadio or Smith. Smith recalls his Southern gentleman boss telling him, “It is my prediction that Mr. Pynchon will be selling used Chevrolets a year from now.” (Strangely, the fate of The Crying of Lot 49 character Wendell “Mucho” Maas.)

After Smith signed on Pynchon for a two-book deal, he and the author — living first in Seattle, working for Boeing, and later in Mexico — largely communicated by mail. Finally Smith received a big black box on his desk containing the manuscript of V. “It was easily the most exciting thing to happen to me in publishing,” Smith says. “It was a burst of virtuosity.” Pynchon’s brilliant “polymath” mind dazzled him through every page of the novel, whose main characters search for the elusive, time-traveling, space-jumping, mirror-crossing “V.” While comically immersed the fringe culture of the fifties, the enigmatic novel, like V. herself, suggests a wild capacity for perpetual self-reinvention.

Although it was a challenge publishing the unknown author, V., released in 1963, received great critical praise, sold out its print run, and won the William Faulkner Foundation First Novel Award. Pynchon quickly wrote his next novel, The Crying of Lot 49, edited by Smith, to fulfill his contract with Lippincott before moving with Smith to Viking. Pynchon almost considered the book a throwaway at the time, but the slim, dense, amazingly intricate novel of paranoia, receding revelation, and an underground postal service has become his most widely read work.

Once Donadio took Pynchon as her client, they developed a strong personal connection that would grow through and beyond the years he spent writing Gravity’s Rainbow, published in 1973. She respected his privacy and rarely talked about him, but their closeness is well-known by the people around her, and reflected in the intensity of their correspondence.Pynchon sometimes stayed for periods of time at her house in Stonington, Connecticut, which Donadio opened up to many of her authors on the weekends. On one visit, Juris Jurjevics met him by chance. “He was passing himself off as a laborer on the house,” he says. “Candida sort of rolled her eyes.”

Donadio, Pynchon, Smith, and his wife, Sheila, would go out for dinner now and then. Smith says that Pynchon was casual and shy, but talkative on certain subjects, especially the movies. “He was a movie freak,” Smith says.

Olson says of Pynchon, “I know there was probably no writer that Candida was closer to in the years that they were together. And no writer whose genius she valued more — maybe several as much, certainly nobody more. And the letters between the two of them, which if Mr. Pynchon has his way will never become public in his lifetime, are clear evidence of what an intense bond there was, and how much he meant to her.”

In its July 4, 1994 issue, The New Yorker ran a “Talk of the Town” piece about a visit with Carter Burden, the collector to whom Donadio sold Pynchon’s letters for $45,000 in 1984. The article reads, “He showed us a slim box containing a hundred and thirty letters from Thomas Pynchon to his then agent, Candida Donadio, in which Pynchon compared her to a guru.”

It continues, “[Pynchon] claimed that reading The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen was keeping him sane.” Donadio sold Matthiessen’s crystalline account of his 1973 journey through the Tibetan highlands, which is also a story of mourning and Buddhist contemplation.

Burden died in 1996, and two years later his family donated his $8 million literary collection, including Pynchon’s letters, to the Morgan Library. The documents, excerpts of which were published in the Times, were set to become available to scholars that fall. Amid the sensation and scandal in the literary world, Pynchon’s lawyer, acting on the part of a furious client, immediately squelched their release.

Behind Donadio’s sale of the letters lay her terrible falling out with Pynchon in 1982. Their break was bound up in the departure of Donadio’s then assistant, Melanie Jackson, who had become romantically involved with Pynchon, and is now married to him.

While Jackson was working for Donadio, the relationship that developed between her and Pynchon set off serious tensions among the three. According to Smith, their dating may have first come to light by way of Donadio’s accountant, who called her attention to a slew of receipts for Chinese takeout among her assistant’s expenses.

When Jackson left the agency, she took Pynchon and a good piece of the client list with her. Pynchon sent a formal letter to Donadio severing their professional relationship, and implicitly, their personal one. It read similarly to the one he sent to Smith, “‘Please be advised that Candida Donadio no longer represents me. Please conduct any further business through Melanie Jackson.'” Donadio rarely spoke about the split, but by all accounts it was devastating to her.

Smith says he wrote an “equally stuffy” note back to Pynchon, then met him for lunch. “I said, ‘Tell me what I don’t know about Candida.’ He said, ‘Well she hasn’t done anything for me in the last few years.’ I said, ‘What was there to do?’ He’d signed a two-book contract for a million dollars, a million dollars in the seventies, without a manuscript. He said, ‘She hasn’t done anything with movies.’ I said, ‘From my understanding, you didn’t want a movie made.’ He wanted script approval — God doesn’t get script approval in Hollywood. Neither he nor I ever mentioned Melanie.”

Pynchon still had a contract with Viking, but when Jackson approached Smith about publishing a book of short stories, and then came back to him with one higher bid and then another, the negotiations struck Smith as “dubious.” Pynchon wanted to be released from his contract, and left for Little, Brown and Company to publish Vineland.

Smith says it wasn’t about money, but about cutting professional ties. “I think Pynchon didn’t want to have anything to do with his old life, which meant Candida and me.”

The surfacing of Pynchon’s private correspondence “was a black eye for Candida,” Smith says.

When news broke of the letters going public, Olson says he was “scrambling to protect myself and protect the agency without really having a clear idea of what had happened.” Donadio was “cloudy” about the details and in poor health. Legally, she had rights to the papers; the publication rights were Pynchon’s.

“I think it was kind of her ‘fuck you’ to Pynchon, to whom she was closer than anybody in the world. In the sense of, you know what, screw you, I’m gonna cash in,” Olson says. “But with the understanding that it was going to a private collector who would keep it private, that was her memory, that those were the terms.

“The Pynchon thing is exceptional, I think it’s exceptional in direct proportion to how much he meant to her as a writer and as a person. And how betrayed she felt by the whole situation, and she did.”

Stone says that he and Donadio found a natural bond. “We had in common these desolate Catholic childhoods, so we spoke that language. And we had a similar sense of humor. So we got closer and closer as time went by.”

“She was certainly a mine of Sicilian proverbs,” he says. (A memorable one: “To trust is good. Not to trust is better.”) “And she used a lot of Yiddish. She was very New York-y. It was something that bound us all together — she and I and she and others … She was very erudite, very well-read, and she read in several languages, in Italian, and in Spanish; she may have read in Portuguese. Now that I think back on her, she seems so unlike anyone who’s around now, that it’s striking. She really seems to have been a person of her time.”

In 1998, when it was clear Donadio was dying, Stone dedicated his novel Damascus Gate to her. “She really was a good agent for me,” he says, adding that she knew how to motivate him to keep writing, even when he was slow or exacting about his work. “I felt I owed her a lot. And I loved her.”

“Oh, I regarded her as a close friend … I really miss her.”

The working relationship between Donadio and Stone — and their particular moment in publishing — is richly recorded in the Robert Stone Papers, a collection of letters that he donated to the New York Public Library. Donadio’s bright, idiosyncratic voice rings through the documents, whose dropped typewriter keys, formalities, and flourishes evoke a lost era of letter writing.

Dear Bob:

How’d you like to have $1750.00 dollars that is? You’d like it. Call Mac Farrell, fast as you can… Mac says if you can settle this new one fast, do the work, he can immediately put through the check and everyone will be happy, bless us all.

Yours,

Candida

Dear Bob:

It is a pure sweetness. I think I am selling the film rights to MIRRORS! This is how it is: I meet Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward (wouldn’t she do a good Geraldine?) via Joe Heller. Newman has started his own film company, The Newman Foreman Company, and I gave the book to John Foreman when he was in New York. He not only knew it, but loved it, and now we are talking terms … So if all goes well, you will wind up with $110,000. Do you like that? I do.

Happily,

Candida

Unfortunately, the movie that came out of that deal was the heavy-handed WUSA, starring Newman and Woodward. Stone despises the film.

Donadio continued to write robust correspondence through her last days. Edward Hibbert recalls, “She had the most wonderfully elegant way of sending a rejection letter to someone. Letters like, ‘Dear Mr. Schmo, I enjoyed “Diary of a Whatever.” I liked, but I didn’t love. I have no passion for it, which I can do without in my private life, but unfortunately not in my professional.’ … And you’d think, what a blessed way, even though the writer’s getting news he doesn’t want, it’s written in that way. And her letters were extraordinary, and I often look at them and I used to enjoy typing them, because they’re terribly funny and again very unconventional.”

She also got back as good as she gave. A particularly colorful rejection letter came from Herman Gollob, an editor at Little, Brown. He loved all the manuscripts she sent him, except for one. “It was about a guy screwing a gorilla,” he recalls. So he sent this note: “Dear Candida, Ape-fucking novels you’re sending me? Love, Herman.” Donadio called him “roaring.” She framed the letter and hung it on her wall.

Gollob, who used to go out for drinks with Donadio, Smith, and editor Alan Williams, calls Candida “a great pal, a great drinking buddy.” He remembers that upon first hearing of her, he asked if she was “screwing all the guys to get clients.” When they finally met she said to him, “You think I fuck to get clients, do you?” He replied, “I meant that as a compliment!” They became great friends.

In addition to her keen eye, Donadio was also known for her faith in unusual sources of inspiration.

“She said she could always tell a hot book because her parrot would chew on it,” Jurjevics says.

Donadio claimed her home came with a ghost, which she called “Mrs.” something. She would have her guests stand in a certain spot, which Jurjevics affirms was colder than the rest of the room. After having a talk with the ghost, she told him, the noise and trouble settled down.

When logic failed in making office decisions (“never her favorite method,” Olson says) she would consult the I Ching, dreams, and other sources of wisdom.

Olson adds, “One second she would be talking what nonsense it was, but she was Sicilian. And there was this whole idea that you didn’t tempt the fates, you paid attention to messages coming to you.”

“I remember her calling me up one time, she had been out that week in April … She was encouraging us to take Good Friday off, and getting rather agitated that we were saying we might come in. I had no idea where she was coming from with all this, but she said, ‘Neil, we don’t know, he may have been the son of GOD.'” So he took the day off.

“There was a wonderful Nelson Algren story,” he says. Algren, author of The Man With the Golden Arm and The Neon Wilderness, had been a treasured client of Donadio’s, but by the eighties his novels had gone out of print. “There’s a guy named Dan Simon who runs Seven Stories Press … He came along and said, ‘I love Nelson. If you let me bring his backlist into print, I promise you these books will stay around,’ and he was as good as his word.” At one point, Olson says, Simon brought in some possible cover images, mostly of “Nelson smoking cigarettes and walking down dusty streets of Chicago,” and showed them to Donadio for her approval; she said they were nice, then looked pensive, and so Simon asked if they were okay. “She said, ‘Let me check with Nelson and I’ll get back to you.'” At that point, Algren had been dead for three years. “She called Simon the next day to say, ‘He likes them. All right.'”Simon, who wrote a tender piece about Donadio’s memorial service for The Nation, recalls their first meeting in her Chelsea office. She came down from the mezzanine smoking, and he remarked to her that the cigarettes would be bad for her health.

“There are times when it’s healthier to smoke,” she said.

“She was really feeling it when she said it,” he says, recalling her fierce expression, eyes bulging. Apparently there was a crisis around Heller.

“Jesus, God, she was intense,” he says.

Donadio had a way of communing with past writers she had worked with, according to Olson. “Not in any kind of spooky, séance sort of fashion, but they were very much alive to her, all of her authors were with her.”

“She always had time for me, because she loved Algren,” Simon recalls. When he brought to her the question of publishing letters that Algren had not wished not to be published, she meditated deeply on what would honor him as an artist.

Donadio once surprised him by calling Algren “sentimental.” “She didn’t mean it in a derogatory way,” he says. “It was a loving and true thing.”

Her devotion to the author may have been warmed by romantic feelings as well. Bruce Jay Friedman says that Algren had proposed to her, but she turned him down. “He would have been a good husband,” he says.

Unfortunately, the marriages she did make were painful ones. In 1965 she was briefly married to H.E.F. “Shag” Donohue, a writer and academic. Donadio represented his work, which included the novel The Higher Animals and a collection of interviews, Conversations with Nelson Algren.

“Oh, Shag,” is the almost inevitable, lamenting response from Donadio’s friends when his name comes up. By most accounts, he was intense, could be charming, and was often drunk and abusive. Wasserman recalls seeing him put Donadio in a headlock, and “she looked terrified.” The two divorced within three months.

Later in the seventies and early eighties she lived with Henry Bloomstein, whom she called her husband, though it’s not clear they were officially married. Bloomstein was a writer, largely of screenplays and teleplays, whose lightweight material never had much success. Stone says, “Henry was kind of doll-like, he wore this bow-tie. She seemed very affectionate toward him, he also seemed affectionate.” They had an unusual relationship, and some speculate that Bloomstein, who eventually moved to the West Coast, was bisexual or gay. Some also say that he sought to advance his career through Donadio. She showed his manuscripts to a number of editors, none of whom accepted them.

Her relationships with Donohue and Bloomstein caused, and resulted from, a great deal of grief. “She was a desperately lonely, unhappy person,” Wasserman says.

Donadio seldom spoke about her family. Her sister lived in Florence, and her brother in California, and they rarely communicated. Gottlieb met her parents, who he says seemed very loving with each other, in a way that might have left out their children. “There were things in her family that were very difficult for her,” he says.

School didn’t offer much solace. Wasserman remembers one story. “When she was ten years old, she had a teacher named Mrs. Brown who had her stand up, and told her she was stupid, fat, and ugly.” Donadio spoke of getting even with that teacher for “ruining her life,” and when she became “red hot,” she felt she showed Mrs. Brown.

It’s no surprise that she took so readily to self-invention.

“Candida was pure fiction,” Wasserman says. “She wrote the greatest unprinted fiction there ever was.”

“She was brilliant, she was eccentric, and she became more eccentric as time went by,” says Robert Lantz, with whom Donadio partnered in 1968.

Her sudden departure from Russell & Volkening to join the entertainment agent came as a shock to many. Wasserman says that just before taking off, Donadio told her she was going to Chicago for a week, and asked her not to open any contracts that came in, and not to give them to Russell, who normally vetted them. When Wasserman refused to do it, Donadio raised a finger to point at her. “All right for you,” she said, and that was the last Wasserman saw of her for years.

That weekend Donadio simply took all her belongings and contracts, drawing red lines through the cover sheets of manuscripts so they couldn’t be submitted. She left a dumbfounded Diarmuid Russell and Heny Volkening to come in Monday and find her gone.

(The blow of Donadio’s exit seemed to age the stately, refined agents, says Wasserman. She remembers Bellow once saying to her, “Oh, Candida’s all right, she only killed two men.”)

Wasserman says that Candida “wanted her agency to be the mafia of literary agencies. She wanted to have the best client list that ever was.”

She nearly achieved it with Lantz, with whom she created a super-agency combining the best of New York publishing and Hollywood stars. “There will never again be a list like the one between us,” says Lantz. “We really had an astonishing office.”At the height of their partnership, Donadio was handling Pynchon, Heller, Puzo, Roth, Friedman, Gaddis, Cheever, Stone, Frank Conroy, Christopher Isherwood, and Gay Talese. Lantz represented such celebrities as Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Bette Davis, Milos Forman, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Lillian Hellman, Peter Shaffer, Yul Brynner, Joe Namath, and Leonard Bernstein. Al Hirschfeld was a lifelong client, and his caricatures still decorate Lantz’s midtown office.

“Some people had the impertinence to die,” Lantz says. A Hungarian born in Berlin, he has a thick accent (“she vas eccentric”) that accentuates his wry humor.

“We had a certain power for a very small office, because of the list … I learned from Candida, there’s great power in quality.

“She had a remarkable instinct for talent. Her relationship with all those people was very close. They loved and trusted her. She made a lot of money, but she didn’t take them on for money,” Lantz says. “She had a very good business sense, but not ugly business sense. She did what was right for the artist.

“It’s a pity she was not a happy lady.”

Lantz and Donadio often worked jointly with clients who were involved with film, television, or theater in addition to literature. Puzo was one such author, and one of Candida’s closest friends — no doubt brought closer by a Sicilian kinship. Lantz recalls closing the deal to sell the film rights for The Godfather.

“Mario wanted $50,000 more. I said, ‘Don’t be silly, take points of it.’ Everyone told him he’d never see a penny,” Lantz says. When the first check came in, it was for $60,000. “Which was not chicken feed at that time.”

Another client they shared was Bruce Jay Friedman, one of Donadio’s first, from her secretarial days. An author of darkly humorous fiction, he wrote plays as well as novels, and was a good friend of Puzo and Heller.

“There was no one like her,” Friedman says. “I always thought she was my private agent, and I’m sure that twenty other people felt the same way.” Over the course of their decades together, Donadio sold twenty-one of his short stories to Esquire, which may have set an authorial record. She also connected him with Gottlieb for his first novel, Stern, published in 1962, and his later breakthrough, A Mother’s Kisses.“I was really spoiled at a certain point,” he says. “Through a good many years, I’d write a story, I’d send it to her, and then in forty-eight hours … I was taking it as a given that I would have a publication. Or if I wrote a book it would go over to Gottlieb, and he read the same night… It was a dreamy kind of situation.”

Like many of her authors, he lived for her approval. “When she said, ‘It’s good, Bruce,’ I was king of the world. When she said, ‘You haven’t done it, Bruce,’ I would die for at least a month.”

Donadio loved an early novel he wrote called “You Are Your Own Hors D’Oeuvres” about a Martha Stewart–type character, and was determined to sell it. In fact, she kept at it for decades, “even after I lost interest,” Friedman says. It was never published.

“I once accused her of being brilliant, and she said, ‘What I am is attuned,'” he says. “I have never been able to come close to replacing her.”

Robert Brown, who as Esquire‘s fiction editor from 1962 to 1968 published many of Friedman’s stories, says, “My success depended to an extent on the fact that Candida liked me.” Some editors would even attempt to boost their reputation by faking lunches with her in their expense reports. She once remarked to Brown, “I had lunch with three different people on the same day.”

Donadio had a knack, as all great agents must, for matching up writers and editors, often by way of her particular intuition. Friedman remembers her saying, “You’d never get along with that editor, because he’s too short.” In later years she connected him with the editor Donald Fine, warning Friedman about his financial sense: “You have to remember, he’s tighter than a clam’s ass.'”

The Lantz-Donadio agency lasted about ten years. By Lantz’s account, Donadio began coming into the office less and less, partly due to the onset of diabetes. Her drinking may have played a role as well. Some believe that the two were never a compatible match and had a difficult break.

Since Friedman was mostly writing film and television scripts, he found himself being repped by Lantz at the time that the partnership dissolved. But later on, when he and Lantz parted ways, he sought out Donadio’s advice.

“Would I take you back? Is that why you’re here?” she shouted at him. “Yes, I’ll take you back.”

And in that way, without quite intending to, he returned to the fold.

He says she was “ninety percent the all-forgiving good mother. She was only critical in the best possible way.”

“You were glad she was on your side,” he adds.

Gottlieb was among the few to ever challenge Donadio. And in the early eighties, when they had their final professional run-in, their declining friendship collapsed for good.

“Well, she lied, and then she was caught. I mean she knew she had done something terrible. She finally was forced to acknowledge it, and I never spoke to her again.

“And we just don’t lie to each other … So it was a serious matter, and dealing with a well-known author and a great deal of money, and the whole thing was just a disgrace. But you know there’s no point, it doesn’t matter, it’s gossip, it’s meaningless.”

He believes her actions came out of desperation. “She had to score, not because she was greedy, it wasn’t as simple as that. It was to prove to herself and to her people that she could pull off the big deal.

“Candida was great at what she did for a long time, and instrumental in some very important careers. But her emotional problems and her neediness got in the way finally, so that it didn’t continue on that level,” Gottlieb says.

Most of Donadio’s colleagues, especially the younger people she supported, never saw the extreme side he describes, though they knew of her troubles. Writers who were struggling often found comfort in her presence.

Smith remembers a party that Donadio threw for Algren, in which he walked into the bedroom to find her rocking the writer Buzz Farbar, who was crying, on her lap. (Farbar, now dead, was incarcerated on drug importation charges in 1984, in a case involving Norman Mailer.)

When Smith came out of the bathroom, she was still rocking him. Farbar leapt up and took Smith to the mirror, telling him he never knew whether people liked him for himself or for his looks. “I said, ‘I can’t help you much,'” Smith says. “The point is that Candida took him seriously. She didn’t really take him seriously, because he was full of it, but she was very kind to him. She didn’t say, ‘Oh cut the crap, Buzz, and go get your forty-third drink,’ she was very kindly. She has a reputation for being tart-tongued and all that, which is true. But she basically took people at face value.”

“She was helpful in times when things were going badly, both creatively and personally,” says Jack Richardson, a playwright and essayist whom Donadio had represented. “People looked to her not just as an agent, but as a friend. Many went to Candida as a divorce counselor, or for psychiatric help. I myself used her in that capacity, unfortunately, several times.”

Gollob says, “There was always a streak of theatrical melancholy, a tragic sense of herself … Once in a while she’d lose an author, and you’d agonize with her.” He thinks toward the end of her career some writers didn’t find her high-powered enough, or felt neglected. Richardson says she could become drunk and forgetful. She wasn’t as tapped into movie and TV deals as some would have liked.

Says Gottlieb, “She was maternal and nurturing to these young guys, then many of them didn’t want that anymore. They became stars and they didn’t want a ‘mamma mia’ any longer. And then she would be distressed.”

Stone says that Donadio rarely spoke of Pynchon or others who left. “It seemed to be so grievous when anybody left her, she seemed to be so grief-stricken, that I didn’t press it. I mean, God, I don’t think I ever would have had the courage to leave her.”

Many of those who knew Candida in her heyday, including Heller, Puzo and Gaddis, have since passed away. Smith, whose bond with Candida remained strong through the decades, died of emphysema in November 2004. With his passing, a connection to a dynamic moment in American letters feels lost as well.

In a significant way, Donadio’s legacy survives because she had the foresight to do what many agents of her generation didn’t, and that was to nurture a younger generation in her field. In the eighties she hired and later partnered with the adored agent Eric Ashworth, who by all accounts had a special warmth and charm; he died of AIDS complications in 1997. She also, of course, mentored Olson and Hibbert, who, along with partner Ira Silverberg, would become her successors. So when she unofficially left the business in the mid-nineties, her agency remained vital. It still represents a number of her longtime authors — among them Stone, Matthiessen, and Michael Herr, as well as the estates of Conroy, Puzo, and Isherwood — and newer authors including Chuck Palahniuk, Adam Haslett, and Gabe Hudson.Even in retirement, when she had cancer, she kept in touch with her agents and writers. She said to Hibbert, just before he took a trip to Hollywood to work on film rights, “‘Listen kiddo, let me give you some advice. Don’t use any long words. They don’t know from tri-syllable words out there. It’s no good.'”

Olson says, “Candida was so damn generous, there were times when she was far too generous. [Melanie Jackson and Malaga Baldi] are successful agents in their own right, but they got their start because they were getting stuff from Candida … Eric Ashworth started as her assistant, I started as her assistant, Edward Hibbert started as her assistant, people who were partners or running the company all came up from nowhere. So she was very generous in bringing people along.”

Today in publishing, agents often need to be editors to an extent — to help polish a book before submitting it — and more and more editors are crossing over to the agent side. Many of them are attracted to the greater autonomy of the profession, and the opportunity to shape an author’s career. “The world that Candida was in, her job was to identify talent and put it together with an editor who could develop that talent. That happens less and less. The development gets done on the agent side,” says Olson, whose own first novel, The Icon, was published in May.

He remembers, “Despite the fact that she was always shaking her finger at us, saying, ‘The clients aren’t your friends, they’re clients,’ she never kept that rule, they were all her friends. Keeping separation from work, and not letting them have your home number and call you on the weekend, everything she told you was everything that she did, they would call her anytime.

“Her most exceptional quality, I would have to say, is just her instinct at that moment in publishing in the 1960s to see a Heller or a Pynchon or a Gaddis. A lot of people, not only then, but many people even now say, ‘Is this genius or is this the biggest con job of the century?’ To see genius there and to really be willing to knock down all the doors … That instinct it took to know that this was not a con job, this was not garbage, this was a new voice. And I don’t know that she would have considered it anything special. She never talked about her own talents as being anything special.”

Donadio died on January 20, 2001, and her memorial service was held at the Church of All Souls in Manhattan. There she received tributes from Olson, Wilson, Smith, and Stone, as well as from Matthiessen, Herr, and Conroy.

Philip Roth came to pay his respects. When Wasserman saw him, among a number of Donadio’s ex-clients, she wondered if a piece of Candida’s wisdom had come back to them: “We don’t know — she could be the daughter of God! I better show up.”

Karen Hudes is a writer and editor in Brooklyn, NY.

Original print photo of Candida Donadio provided by Neil Olson; digital image courtesy of Karen Hudes.

Beautiful piece. It’s nearly impossible to find information on this woman anywhere, so thank you for shining a light on this wonderful figure of American letters.

Thanks, Poncho, I appreciate that.

I very much enjoyed reading this article and thinking about how life was back then, for editors and literary agents…what a time it must have been. Thank you for doing the research!

Thanks, Alan!

Candy was my second cousin and I did not even realize the extent of her amazing career !

I recently discovered her letters to Philip Roth at the Library of Congress. I would love to get in contact with you for more information if possible

Liz, I’d love to find out more. Please feel free to email me at karen [at] karenhudes.com.