If only measured by his influence on our culture, Thomas Pynchon is an iconic writer. His name is known to many who have never read a word of serious literature, and “Pynchonesque” seems to have as many interpretations as the identity of the mysterious V. in his first novel, V. Pynchon’s earliest writings leapt onto the scene to accolades rarely given to a new author, and he was hailed as one of the bright stars of a new literary generation. His first novel was a winner of major national awards and his magnum opus, Gravity’s Rainbow, nearly won a Pulitzer Prize (more on this later). His subsequent efforts have not failed that early promise.

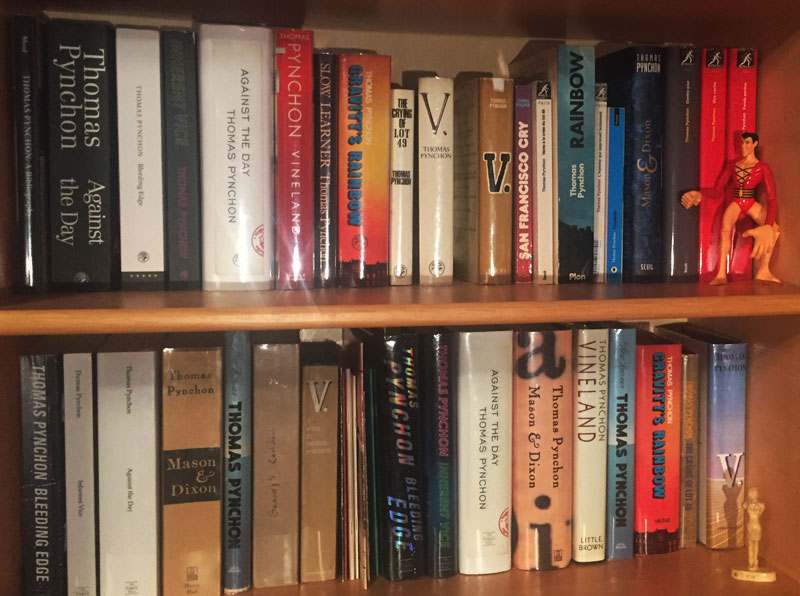

Pynchon’s novels feature dense, convoluted plots, with wide-ranging allusions to history, science, technology, mathematics, and popular culture. One does not just “crank out” works that offer such challenges and rewards to their readers. Indeed, Pynchon has produced just eight novels over the past fifty years. Fortunately for the collector, the existence of variant forms of his novels and of many associated publications can make collecting Pynchon a challenge worthy of that found in reading his books.

Clifford Mead’s Extensive Pynchon Bibliography

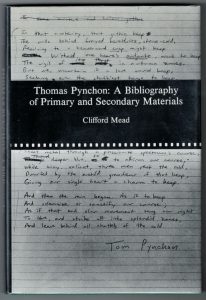

An essential reference for the Pynchon collector is Clifford Mead’s 1989 book, Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources.[1] Although written 27 years ago, it remains the best description of the author’s early works. In addition, it includes the first appearance in book form of Pynchon’s juvenile writings. The presence of these contributions from young “Tom” to his high school newspaper makes Mead’s work a collectable Pynchon text as well as a bibliography.

An essential reference for the Pynchon collector is Clifford Mead’s 1989 book, Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources.[1] Although written 27 years ago, it remains the best description of the author’s early works. In addition, it includes the first appearance in book form of Pynchon’s juvenile writings. The presence of these contributions from young “Tom” to his high school newspaper makes Mead’s work a collectable Pynchon text as well as a bibliography.

Technical Writings for Boeing – Aerospace Safety and BOMARC Service News

Notorious for keeping his personal information private, Pynchon can make Salinger look like a publicity hound. It is known that he studied at Cornell, and that Vladimir Nabokov was one of his professors. Prior to pursuing his career in literature, Pynchon served in the U.S. Navy and then worked at the aircraft company Boeing as a technical writer. The abundance of military and technical references in his books indicates how much these experiences informed his writing. Pynchon’s articles in Aerospace Safety and BOMARC Service News are not only informative, but fun to read, even given their highly technical content.[2] BOMARC Service News poses an interesting challenge for both the academic and the collector, since none of its articles are credited. Textual analysis has identified articles that can be credited to Pynchon with varying degrees of certainty and the magazine issues containing these are rare and quite collectable.

Notorious for keeping his personal information private, Pynchon can make Salinger look like a publicity hound. It is known that he studied at Cornell, and that Vladimir Nabokov was one of his professors. Prior to pursuing his career in literature, Pynchon served in the U.S. Navy and then worked at the aircraft company Boeing as a technical writer. The abundance of military and technical references in his books indicates how much these experiences informed his writing. Pynchon’s articles in Aerospace Safety and BOMARC Service News are not only informative, but fun to read, even given their highly technical content.[2] BOMARC Service News poses an interesting challenge for both the academic and the collector, since none of its articles are credited. Textual analysis has identified articles that can be credited to Pynchon with varying degrees of certainty and the magazine issues containing these are rare and quite collectable.

Pynchon’s Contributions to Literary Journals

Only slightly less difficult to locate are Pynchon’s earliest contributions to literary journals. The March 1959 issue of Cornell Writer and the Spring 1959 issues of Epoch haven’t been seen on the market for several years, so a price is hard to set, but a copy of either would certainly bring several hundred dollars. Later magazines with Pynchon contributions are a bit more common, but still quite collectable, in part, perhaps, because he wrote so few of them.

Thomas Pynchon’s Early Short Stories

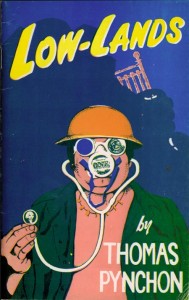

The difficulty in finding these stories, and the high level of interest in Pynchon, led to their appearance in several unauthorized booklets. The first of these, appearing in 1976, was Mortality and Mercy in Vienna, containing a story initially published in Epoch. At least four, and as many as six variants of the first edition of this booklet are known, identified by varying ink colors and the position (or absence) of the registration marks used to produce its multicolored cover. Two years later the same press brought out Low-Lands, which had first appeared in New World Writing 16. As an aside, the cloth bound edition of NWW16 has the honor of being the first appearance of Pynchon in hardcover. From 1980 to 1983, one such booklet appeared each year: The Secret Integration (originally found in The Saturday Evening Post), Entropy (first published in Kenyon Review 2), The Small Rain (Pynchon’s first published story – from Cornell Writer), and A Journey into the Mind of Watts (an essay originally found in the New York Times Magazine). The success of these booklets is proven by the fact that all but one of them went into second editions. Of course, the publication of such piracies did not please their author, but they have become objects of desire for the serious Pynchon collector.

The difficulty in finding these stories, and the high level of interest in Pynchon, led to their appearance in several unauthorized booklets. The first of these, appearing in 1976, was Mortality and Mercy in Vienna, containing a story initially published in Epoch. At least four, and as many as six variants of the first edition of this booklet are known, identified by varying ink colors and the position (or absence) of the registration marks used to produce its multicolored cover. Two years later the same press brought out Low-Lands, which had first appeared in New World Writing 16. As an aside, the cloth bound edition of NWW16 has the honor of being the first appearance of Pynchon in hardcover. From 1980 to 1983, one such booklet appeared each year: The Secret Integration (originally found in The Saturday Evening Post), Entropy (first published in Kenyon Review 2), The Small Rain (Pynchon’s first published story – from Cornell Writer), and A Journey into the Mind of Watts (an essay originally found in the New York Times Magazine). The success of these booklets is proven by the fact that all but one of them went into second editions. Of course, the publication of such piracies did not please their author, but they have become objects of desire for the serious Pynchon collector.

Of a Fond Ghoul: Pynchon’s Correspondence with his V. Editor

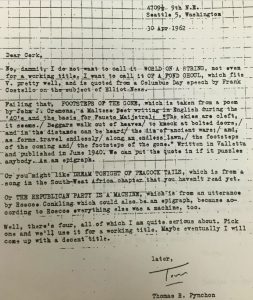

Also unauthorized was the 1990 publication of a collection of letters between Thomas Pynchon and his erstwhile editor Corlies M. “Cork” Smith in a slim volume entitled Of a Fond Ghoul. The 1962 letters concern the preparation of V. for publication and provide rare insights into Pynchon’s writing process. Of the 50 numbered copies, three have shown up on the market in the last decade, each commanding a significant price.

Also unauthorized was the 1990 publication of a collection of letters between Thomas Pynchon and his erstwhile editor Corlies M. “Cork” Smith in a slim volume entitled Of a Fond Ghoul. The 1962 letters concern the preparation of V. for publication and provide rare insights into Pynchon’s writing process. Of the 50 numbered copies, three have shown up on the market in the last decade, each commanding a significant price.

Pynchon’s Blurbs for Other Writers

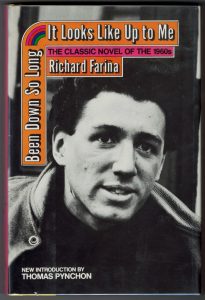

Because of the paucity of available materials, many Pynchon collectors tend to accumulate anything containing Pynchon writing. The presence of a Pynchon blurb on the back cover increases the value of any book. Of even more interest are the books where Pynchon provided an introduction. The first of these, and the most collectable, is the third edition of Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me (Viking, 1983), the first (and only) novel by his friend Richard Fariña whose untimely death at 29 in 1966 was devastating to those who knew him. Pynchon was his close friend and roommate at Cornell and the best man when Fariña married Mimi Baez in 1963. His introduction to this later edition of Been Down (first published in 1966 by Random House) is a moving reminiscence of his time spent with Fariña, and provides great biographical information and insights.

Because of the paucity of available materials, many Pynchon collectors tend to accumulate anything containing Pynchon writing. The presence of a Pynchon blurb on the back cover increases the value of any book. Of even more interest are the books where Pynchon provided an introduction. The first of these, and the most collectable, is the third edition of Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me (Viking, 1983), the first (and only) novel by his friend Richard Fariña whose untimely death at 29 in 1966 was devastating to those who knew him. Pynchon was his close friend and roommate at Cornell and the best man when Fariña married Mimi Baez in 1963. His introduction to this later edition of Been Down (first published in 1966 by Random House) is a moving reminiscence of his time spent with Fariña, and provides great biographical information and insights.

Miscellaneous Other Pynchon Gems

In addition to the materials described above, the diligent collector might find some other items that are not so easy to classify. The 1976 Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Art and Letters includes a copy of an interesting letter in which Pynchon attempted to decline the offer of a prestigious award. Pynchon’s action when told the award couldn’t be rescinded is classic. He sent Professor Irwin Corey in his stead, leading to the most bizarre acceptance speech in the history of literary award banquets. Just to add to the surreal nature of the moment, a streaker chose that moment to cross the stage.[3]

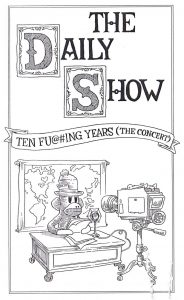

When Jon Stewart planned the concert celebrating ten years of The Daily Show, he asked Pynchon to write an introduction to the program. Pynchon responded with “The Evolution of the Daily Show”, and finding a copy of that program would bring a smile to the face of any Pynchon collector. You can download a PDF of the full program here.

When Jon Stewart planned the concert celebrating ten years of The Daily Show, he asked Pynchon to write an introduction to the program. Pynchon responded with “The Evolution of the Daily Show”, and finding a copy of that program would bring a smile to the face of any Pynchon collector. You can download a PDF of the full program here.

When the school attended by Pynchon’s son requested articles from parents for inclusion in their newsletter, I don’t imagine they hoped for a response from Pynchon. But they got one, and the newsletter containing “Hallowe’en Over Already?” has become one of the most sought after elementary school publications ever printed.

Thomas Pynchon’s Novels and Short Stories

But of course, any Pynchon collection must center on his eight novels and one collection of short stories. The rest of this article will concentrate on these.

Discussing Pynchon’s books is a dangerous path to pursue, for peeling back and examining each layer of allusion, detail, and meaning uncovers a new inner layer that seems even more complex. It’s tempting to try to continue with finer and finer analysis until there is no more to discover. But that’s been attempted numerous times, and no one has found where Pynchon’s literary “Planck length”, beyond which no further detail can be resolved, lies.

So I’ll leave the detailed summary and analysis of these works to the numerous books, journals and websites dedicated to such. Instead, in what follows, I’ll provide just a few details to evoke a bit of the nature of each work and then concentrate on the first publication of each and the variants that might attract the interest of the Pynchon collector.

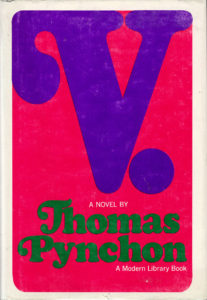

V. (1963)

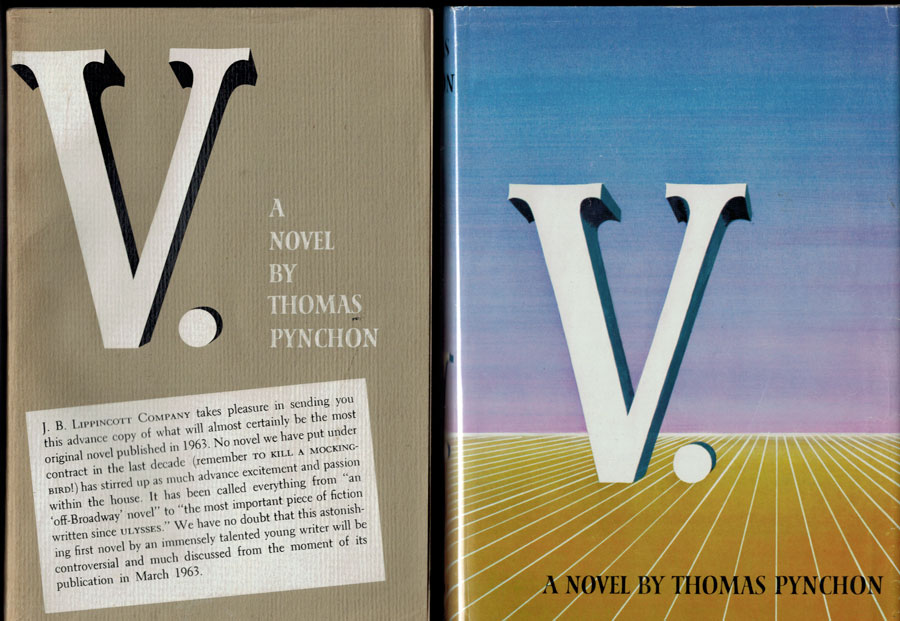

When someone asks me what V. is about, I never know what to say. One even has trouble pinning down to whom, or what, the title refers. Is it Valetta, Malta, or Vheissu, Venezuala? Is it the 19th century beauty Victoria Wren living in Egypt, or the 20th century rat Veronica living in the sewers of New York? Or is it the structure of the novel, which follows two converging story lines, one involving the geopolitical Great Game of the 1800s, the other the antics of “The Whole Sick Crew” in New York? Regardless of, or perhaps partly because of, its complexities, V. was widely hailed when published, winning the William Faulkner Foundation award for best debut novel and being nominated for a National Book Award.

- Publisher’s Review Slip

- Modern Library Edition (1966)

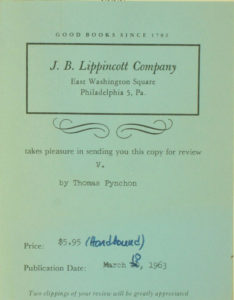

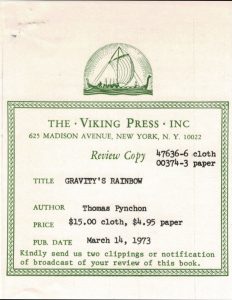

Publisher’s Review Slip[/caption]Prior to publication, an Advanced Reading Copy (“ARC”) was released in sage-gray wrappers. The book was subsequently published in England by Jonathan Cape, with a very limited printing of ARCs in red wrappers. Like all of Pynchon’s British first editions, it’s frequently collected. The British edition of V. is of particular interest, since it includes textual corrections from Pynchon that didn’t appear in any U.S. edition for several years due to a falling out between Pynchon and his publisher, Lippincott.[4]

In 1966, the Modern Library published V. as part of their “Modern Fiction” series. Collectable copies can fetch $200-$300.

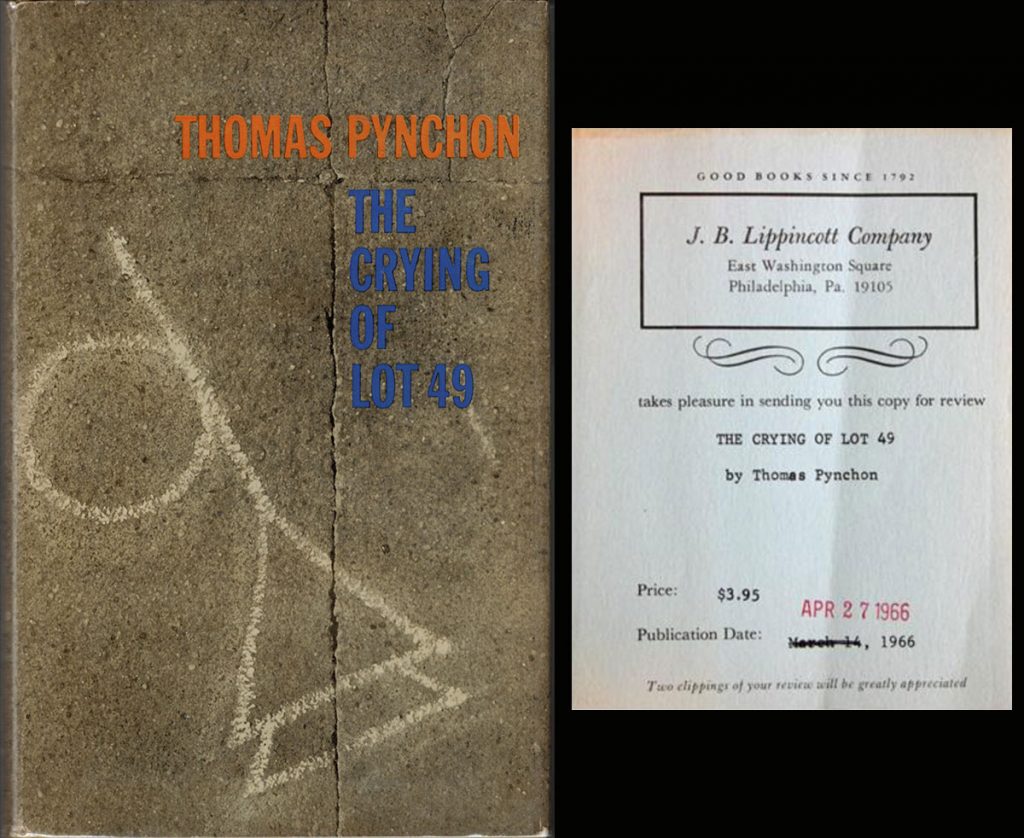

The Crying of Lot 49 (1966)

Of his second book Pynchon has written, “The next story I wrote was The Crying of Lot 49, which was marketed as a ‘novel,’ and in which I seem to have forgotten most of what I thought I’d learned up until then.”[5] Nevertheless, this is the Pynchon work that is most commonly featured in literature classes. His shortest and most tightly written book contains themes of conspiracy and paranoia that have become Pynchon hallmarks. Its use of extensive, and often obscure, popular culture references is also seen in his subsequent works. In return, the book itself is often referred to in popular culture, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to Radiohead and Mad Men.

With Lot 49, Pynchon’s dislike of producing proofs (aka galleys, Advance Reading Copy) is first seen. Only a very few copies of the uncorrected proof were released and I know of none offered for sale for decades, nor have any photos of such an ARC turned up. The only evidence of its existence is a mention in Clifford Mead’s Bibliography: “Note: this first edition [of Lot 49] was preceded by an uncorrected proof copy in yellow wrappers in a plastic spiral binding.” (Mead, p. 9). However, copies of the first edition were distributed by Lippincott with a publisher’s slip laid in, and these command a premium price.

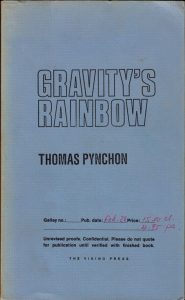

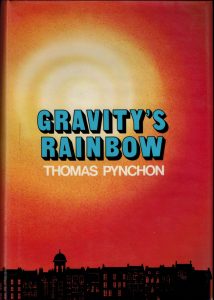

Gravity’s Rainbow (1973)

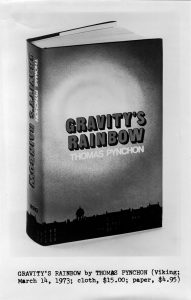

Gravity’s Rainbow is widely regarded as both Pynchon’s masterpiece and his most difficult work. The recognition of its challenges is sufficiently widespread that they were featured in an episode of The Simpsons, where rereading Gravity’s Rainbow is humorously presented as a sign of both literary acumen and pomposity. The book’s title is an overt reference to the parabolic flight taken by the German V-2 missiles subsequent to engine burn out, but like much of the text, it’s subject to other, more subtle interpretations. With over 400 characters and multiple plot lines that are intertwined like strands of spaghetti, this work immerses the reader in a flood of technology, songs, proverbs, popular cultural, historical incidents, and outlandish behavior. Almost all reviews of the book glowed with praise, and in 1974 Gravity’s Rainbow shared the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction. The subsequent year it was selected for the William Dean Howells Award as the best novel over a five year span. The 1974 Pulitzer Prize jury on fiction made Gravity’s Rainbow its sole selection for the year, but the Pulitzer board rejected it, calling the book “turgid, overwritten, and obscene”, and did not award a prize for fiction that year.

- Advance Galleys/Proofs

- Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon, 1973

- Review Slip

- Photo for Reviewers

Gravity’s Rainbow is a massive book, issued simultaneously in a hardback trade edition, a Book of the Month Club edition, and as a trade paperback. All three are collectible, but it is the hardback trade edition that is most desirable, especially since the first issue was comprised of only 4,000 copies. Initially it was thought that no proof copies were issued, and that the only “special” copies were those with the publisher’s review slip laid in. However, a decade after the book’s release a few uncorrected proofs in blue wrappers started to be offered for sale. Textual differences between this proof and the published edition (most notably to the epigraph quoted for Part 4) only add to the interest in this proof. There was also a small printing of galleys for the UK edition of Gravity’s Rainbow, in decorated red wrappers. [How to Identify a Gravity’s Rainbow First Edition]

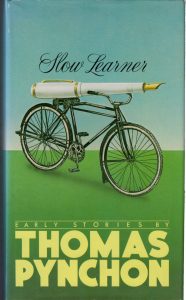

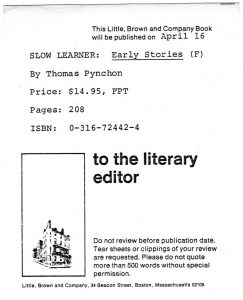

Slow Learner (1984)

The piracies of Pynchon’s short stories that appeared after Gravity’s Rainbow may have be part of the impetus for Pynchon to bring out Slow Learner, a collection of his early short stories. The book is particularly notable for Pynchon’s introduction, which offers rare autobiographical comments as he provides his thoughts upon revisiting the stories and his recollection of events surrounding their creation. While no proofs or ARCs were issued, copies of the first edition with a publisher’s review slip laid in sell at a premium. Much more valuable, however, is a very limited edition of 20 copies of the unbound, sewn signature sheets for the book, laid in an untrimmed copy of the dust jacket. These do come on the market, but not often.

- Vineland, US First Edition

- Review Slip

- Unbound Advance Proofs

Vineland (1990)

It was 17 years between Gravity’s Rainbow and Pynchon’s next novel, Vineland. To say that his new book was greatly anticipated would be a gross understatement. With such a build up, it might not be surprising that it was hard to live up to the expectations of most reviewers. A notable exception was Salman Rushdie’s positive review in the January 14th, 1990 edition of the New York Times Book Review, a magazine sought by both Pynchon and Rushdie collectors. Pynchon and his editor Ray Roberts were making changes to Vineland right up to the day it went to press, so even if they had been desired, proofs or ARCs would not have been practical. However, the Little, Brown Publicity Department needed material, so about five photocopies of an early draft were bound in black plastic spiral binders. Of interest as both the only early issue of this book and for the textual differences that expose some of Pynchon’s writing process, any purported copy must be carefully checked for provenance and authenticity, since a photocopy of one of the original five could be difficult to detect. Again, first editions of Vineland are found with a publisher’s review slip laid in. And once again, a “special” issue was made of sewn, unbound signatures, this time laid in the standard first issue dust jacket. Since only eight of these were produced, they are almost never seen for sale.

- First Edition

- Press Release / Review Slip

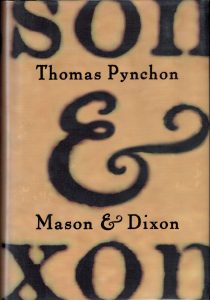

Mason & Dixon (1997)

When Mason & Dixon appeared, it was praised as a welcome return to form for the writer. The noted critic Harold Bloom thought it the best of Pynchon’s works to date.[6] This very large work, which Pynchon had worked on for over 20 years, follows a greatly “enhanced” story of the surveyors of the Mason-Dixon line during the birth of the American Republic. Rather than offering a simply historical narrative, Pynchon gives us a variety of views of a panoply of stories, with the structure of the work reflecting the ambiguity and uncertainty that is always found in actual historical accounts.

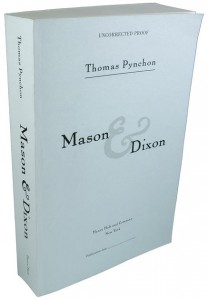

- US ARC

- US First Edition

- Press Release

With Mason & Dixon, Pynchon had moved to a new publisher, Henry Holt. Perhaps that’s why the offering of pre-publication copies was handled so differently from the author’s other works. Around 15 copies of an uncorrected proof were printed in blue wrappers. In the printing of this proof, the title page ampersand in “Mason & Dixon” was unintentionally reduced to a faint shadow. In all but two of these proofs this title page was excised and a corrected page was tipped in, leading to two separate issues. Much more common are the ARCs of this book, issued in beige wrappers. These were produced in two variants of 500 copies each, with the only difference being the back cover, where one version (sent to reviewers) had a plot summary and the other (sent to bookstores) had publication information. In addition, copies of the first edition are found with a publisher’s review slip and promotional information laid in.

Against the Day (2006)

Nine more years would pass before Pynchon’s Against the Day was published. This longest of Pynchon’s novels follows over 100 characters across three continents. The title is often said to refer to II Peter 3:7 (“But the heavens and the earth,… are kept in store, reserved unto fire against the day of judgment and perdition of ungodly men.”), although I’ve always preferred the use of the phase in II Timothy1 1:12 (“…he is able to keep that which I’ve have committed unto him against that day.”), which can offer either doom or hope.

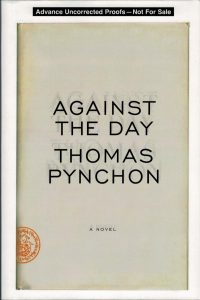

- US ARC

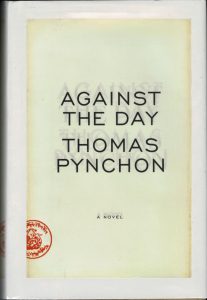

- US First Edition

- Press Release

A typically, Pynchon offered his own pre-publication synopsis of the work, stoking the fever of interest that always accompanies a new Pynchon text. The novel, set “between the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and the years just after World War I”, moves across North America, Europe, Asia “and one or two places not strictly speaking on the map at all.” While there is one traditional plot line that runs through the novel, it is almost overshadowed by the numerous subplots and often confounding episodes that are introduced, dropped and re-encountered throughout the book. Louis Menand of the New Yorker claims this “was all surely part of the intention, a simulation of the disorienting overload of modern culture.”

The first edition was preceded by a small number of uncorrected proofs sent out for review purposes. To maintain security prior to publication, each proof had the name of the reviewer and their organization inscribed in heavy black marker on the title page (although unmarked ARCs have been spotted in the wild). Copies of these proofs are just starting to appear for sale, but the price is by no means established. Copies have sold for as little as $450, and been offered (but not sold) for as much as $3,500. As with many of Pynchon’s other works, copies of the first edition are found with a publisher’s review slip and promotional information laid in.

Interestingly, there are two variants of the first (and only) hardback editions. On one, the boards are beige with a reddish-brown spine; on the other, the boards are a light sage with a dark green spine. I’ve not noticed any particular preference with collectors or difference in value.

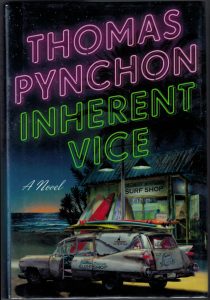

Inherent Vice (2009)

Pynchon’s next book, Inherent Vice, offers more mainstream appeal than his previous works and appeared to mainly positive reviews, even if many, like the New York Times‘ Michiko Kakutani, called it “Pynchon Lite.” Second only to The Crying of Lot 49 in brevity, the book follows L.A. private investigator Doc Sportello as he attempts to foil a plot to have his client confined to a mental institution. A taste of Pynchon’s energy and themes of paranoia and the counter-culture are present, but in a much more accessible format.

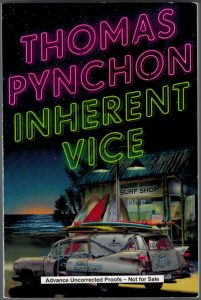

- US ARC

- US First Edition

- Press Release

- Review Letter

Once again, this book was preceded by a small number of uncorrected proofs sent out for review purposes, with each proof having the name of the reviewer and their organization inscribed in heavy black marker on the title page. Just a few copies of these proofs have started to appear for sale, and even a ballpark range for the price is not yet established.

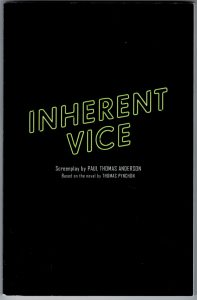

Screenplay for the “Inherent Vice” Film by P.T. Anderson

In 2014, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson transformed this book into the first and only Pynchon-based movie adaptation. Reviews were mixed, with Anderson’s screenplay nominated for an Oscar. To support this nomination, the studio produced a limited number of softbound copies of the screenplay for members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. While Pynchon did not write this work, it does make a nice addition to a Pynchon collection.

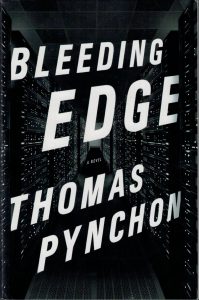

Bleeding Edge (2013)

In 2013, Pynchon turned 76, but he was not done yet. Bleeding Edge, his eighth novel, takes place in Manhattan’s Silicon Alley during “the lull between the collapse of the dot-com boom and the terrible events of September 11.” As with it’s predecessor, some critics complained that the book didn’t contain the complexity or depth of Gravity’s Rainbow and Against the Day. On the whole, however, the book was well received and was named a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. The book is more mellow than some of its predecessors, and perhaps Pynchon has mellowed, too. Copies of the ARCs for were produced and they were released without the security of being inscribed with a reviewers name. Accordingly, the ARC for this book is a good bit easier to find than those of other Pynchon books, and considerably less expensive.

- US ARC

- US First Edition

- Press Release

- Review Letter

Will the Collectibility of Thomas Pynchon Hold?

In Ada (1969), Nabokov refers to “the collected works of unrecollected authors.” It is a certainty that many collections of today’s highly sought writers will one day find themselves in that category, the “Beanie Babies” of tomorrow. But even the most paranoid of Pynchon collectors need not fear that fate. The breadth and depth of his writing offers new insights and pleasures whether reading his books for the first time or for the tenth. His influence on subsequent literature is undeniable, and he has been credited with “redefining both postmodernism and the novel in general.” The extent to which he captures his zeitgeist has been compared to the fullness in which Rabelais, Melville, and Joyce captured theirs. We can reasonably expect that Pynchon, like them, will remain in the pantheon of literature’s greats, and that, in collecting his works, we preserve some of the very best writing of our time.

Footnotes

- Clifford Mead, Thomas Pynchon: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Materials, The Dalkey Archive Press, 1989 (Purchase on ABEBooks.com)

- Adrian Wisnicki, “A trove of new works by Thomas Pynchon? Bomarc Service News rediscovered”, Pynchon Notes 46, Page 9, Fall 2000

- The Official Site Of Irwin Corey.

- Rolls, A., (2012). “The Two V.s of Thomas Pynchon, or From Lippincott to Jonathan Cape and Beyond” Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon.

- Pynchon, Thomas R., Introduction to Slow Learner (Little, Brown, 1984)

- Bloom, Harold. Thomas Pynchon (Bloom’s Major Novelists), 29 April 2013

Related Links…

- How to Identify a Gravity’s Rainbow First Edition — Hardback and Softcover

- Article about Clifford Mead and his retirement from Oregon State University.

- The Pynchon Wikis — A wiki for each of Pynchon’s novels

- Ken Lopez Bookseller — Ken is a longtime purveyor of Pynchon’s books and ephemera. His bookshop is located in Hadley, MA

- Waverly Books — Located in Santa Monica, CA, this is another bookseller focused on Pynchon and modern fiction in general.

Robert Nelson

In addition to being an obsessed Pynchon collector, Robert Nelson trained in Mathematics and Physics at the University of Michigan and Cornell before co-founding Airflow Sciences Corporation, an engineering firm specializing in solving fluid flow problems such as reducing pollution from power plants, helping bring medicines to market, improving the performance of sporting equipment, and much more. His love of fine literature, popular culture, and technology makes Pynchon’s writings one of the many loves of his life, although they do take a secondary place in that regard to his wife Nancy and daughter Patricia (who’s a literary agent). Other interests include his church, choral music and stage performance, and taking any opportunity to teach kids the joy of science. [Visit his website]

Hoping to find or understand Thomas makes as much sense as the ignorant American tourist standing outside a Hindu temple in Beijing and asking the starving widow with no teeth where god is. It’s a hell of an article. Fucking brilliant.