By Thomas Pynchon.

896 pages.

Viking. $15; paperback, $4.95.

This review, by American literary critic Richard Poirier (1925 – 2009), which first appeared in The Saturday Review (1924 – 1986) on March 3, 1973, is one of the first reviews of Thomas Pynchon’s third novel. It is detailed and insightful and is, in fact, a great read before tackling Gravity’s Rainbow for the first time. What I find truly amazing is Poirier’s depth of understanding of Pynchon’s 760-page novel which he’d probably had for maybe a month or so, as it was published on February 28, 1973.

From The New York Times Obituary: “Mr. Poirier (pronounced to rhyme with “warrior”) was an old-fashioned man of letters — a writer, an editor, a publisher, a teacher — with a wide range of knowledge and interests. He was a busy reviewer for publications from The New York Review of Books to The London Review of Books, and his reviews could sting.”

Poirier also wrote excellent reviews of V. (The New York Review of Books), The Crying of Lot 49 (New York Times), and Slow Learner (The London Review of Books).

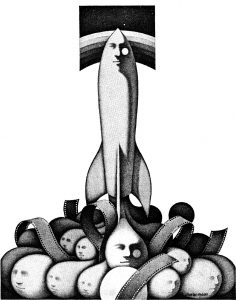

The fantastically variegated and multi-structured V., which made Thomas Pynchon famous in 1963 and the wonder ever since of anyone who has tried to meet or photograph or interview him, is the most masterful first novel in the history of literature, the only one of its decade with the proportions and stylistic resources of a classic. Three years later came The Crying of Lot 49, more accessible only because very much shorter than the first, and like some particularly dazzling section left over from it. And now Gravity’s Rainbow. More ambitious than V., more topical (in that its central mystery is not a cryptogram but a supersonic rocket), and more nuanced, Gravity’s Rainbow is even less easy to assimilate into those interpretive schematizations of “apocalypse” and “entropy” by which Pynchon’s work has, up to now, been rigidified by his admirers.

At thirty-six, Pynchon has established himself as a novelist of major historical importance. More than any other living writer, including Norman Mailer, he has caught the inward movements of our time in outward manifestations of art and technology so that in being historical he must also be marvelously exorbitant. It is probable that he would not like being called “historical.” In Gravity’s Rainbow, even more than in his previous work, history — as Norman 0. Brown proposed in Life Against Death — seen as a form of neurosis, a record of the progressive attempt to impose the human will upon the movements of time. Even the very recording of history is such an effort. History-making man is Faustian man. But while this book offers such Faustian types as a rocket genius named Captain Blicero and a Pavlovian behaviorist named Edward Pointsman, it is evident that they are slaves to the systems they think they master.