On March 1, 1973, the Library Journal published a review of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, with the reviewer Bruce Allen declaring Pynchon’s third novel to be “the most important work of fiction yet produced by any living writer.” But Allen also wrote to Viking, the novel’s publisher, complaining about the $15 cost of the hardback edition.

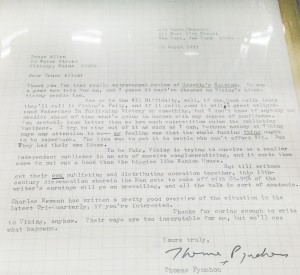

Pynchon appreciated Allen’s review but, more importantly, he understood Allen’s complaint about the price and, in a letter — dated March 25, 1973 — attempted to shed some light on Viking’s reasons as well as his own feelings on the matter. The letter (on the usual quadrille paper):

Dear Bruce Allen:

Thank you for that really extravagant review of Gravity’s Rainbow. It was a good ego trip for me, and I guess it must’ve cheered up Viking’s advertising people too.

Now as to the $15 Difficulty, well, if the book sells lousy they’ll call it Viking’s Folly, and if it sells good it will be a great enlightened Watershed In Publishing History or something, but I don’t know if anybody can predict ahead of time what’s going to happen with any degree of confidence. You probably know better than me how much superstition rules the publishing business. I try to stay out of it as much as I can, because nobody at Viking pays any attention to me– my feeling was that the whole fucking thing ought to be paperback. The idea was to get it to people who can’t afford $15. But They had their own ideas.

To be fair, Viking is trying to survive as a smaller independent publisher in an era of massive conglomeratizing, and it costs them more to put out a book than the biggies like Random House.

But till writers get their own publishing and distributing operation together, this 19th-century dispensation wherein the Man gets to make off with 85-95% of the writer’s earnings will go on prevailing, and all the talk is sort of academic.

Charles Newman has written a pretty good overview of the situation in the latest Tri-Quarterly, if you’re interested.

Thanks for caring enough to write to Viking, anyhow. Their ways are too inscrutable for me, but we’ll see what happens.

Yours truly,

Thomas Pynchon

My writing this post was triggered by a visit to the 48th California International Antiquarian Book Fair, in Oakland, CA. Right next to noted Pynchon dealer Ken Lopez‘s booth, was the Between the Covers Rare Books booth where I saw the letter for sale, in an archive that contained other Pynchon-related (though not Pynchon-generated) items, the advance bound manuscript and first hardback edition of Gravity’s Rainbow. Price: $35,000! So I took a pic of the letter:

Marketing Gravity’s Rainbow

Gerald Howard writes about the marketing of Gravity’s Rainbow in a Pynchon-themed edition of Bookforum (Summer 2005):

Now the real problem presented itself: How to publish a seven-hundred-plus-page book at a price that would not be grossly prohibitive for Pynchon’s natural college and postcollegiate audience. V. and The Crying of Lot 49 had each sold more than three million copies in their Bantam mass-market editions. (Let us pause here to contemplate what these numbers say about the extent of literacy in the America of the ’60s. Then I suggest we all commit suicide.) According to a letter from Cork Smith to Bruce Allen (who reviewed Gravity’s Rainbow for Library Journal but wrote to Viking complaining about the novel’s price), Viking would have had to sell thirty thousand copies at the then unheard of price of $10 just to break even. By comparison, V. and The Crying of Lot 49 had sold about ten thousand copies apiece in hardcover. So how to reach even a fraction of the cash-strapped Pynchon-loving millions? Cork himself hit on the then unique strategy of publishing an original trade-paperback edition at $4.95 and “an admittedly highly priced hardcover edition” at $15, each identical in paper stock and format, differing only in their binding. The gamble: “We also thought that Pynchon’s college audience might, just might, be willing to part with a five-dollar bill for this novel; after all, that audience spends that amount over and over and over again for long-playing records.” The other gamble was with the reviewers, who rarely took paperback fiction seriously, but as Cork wrote, “We feel—as, clearly, you do—that Pynchon cannot be ignored.”

Thus locked and loaded, Viking proceeded to do what it did as well as any American publisher in those days: generate high-end literary anticipation and excitement. The advance galley and complimentary copy lists in the editorial file offer a vividly detailed snapshot of elite American literary culture circa 1973. Bound proofs were sent for possible blurbs and general buzz generation to the likes of Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Leslie Fiedler, Frank Kermode, Ken Kesey, William Gaddis, Benjamin DeMott, Paul Fussell, John Updike, John Cheever, George Plimpton, Lionel Trilling, Richard Ellmann, Kurt Vonnegut, and similar folks. In the file there is a memo, in Cork’s hand, in which are written the names Heller and Puzo, both Donadio clients, and alongside them the annotation “still trying to get through V.” Richard Poirier was sent a very early photocopy of the manuscript by Elisabeth Sifton, the superb editor just then starting out at Viking. There is a much longer list of people who received complimentary copies, which spreads an even wider net among writers and review editors, and included as well a great many publishing figures, some still around, some sadly gone (I had not thought death had undone so many). It also includes, amusingly enough, the recently departed actor Jerry Orbach and the society bandleader Peter Duchin. One complimentary copy is so puckishly hilarious that its accompanying letter, from Kennebeck, needs to be quoted in full. It is addressed to Fairchild Industries in Germantown(!), Maryland, and reads, “Dear Dr. Von Braun: I am sending you herewith a copy of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, with the compliments of the author.”

Yes, Gravity’s Rainbow not only established Pynchon’s place in the Writers Pantheon, but its publication was both innovative and controversial.

And, of course, if you’d snagged one of the 4,000 first printings for $15 and kept it in good shape, you’d have a pretty valuable book in your collection.

One thing I would like to share. I am in possession of a 1973 Chinese pirated

edition of the classic. I have never seen this anywhere else, or even heard

about it from anyone else. I am sure Pynchon himself would be amused. Now

this is in English mind you, with red boards and flaking gilt on the spine. The

Chinese contempt for intellectual property must go back a hell of a long way.

Imagine the reluctant student purchasers of the $15 Viking, grinning as they

handed over a couple of bucks to the Village sidewalk peddlers. You got to love it.

Hah! So this was a pirated Gravity’s Rainbow sold in the USA? Too much. And the text is unchanged? (I imagined it being translated into Mandarin or Cantonese and then back to English…).

If you can provide me high-res scans of the book, I’ll include it in the Cover Art for Gravity’s Rainbow section of this site.

“this 19th-century dispensation wherein the Man gets to make off with 85-95% of the writer’s earnings”

Whose earnings??? Writers sign a contract w/ the publisher who edited, published, promoted, printed, and distributed it. If they don’t like it they can always be Joyce and vanity print it.