Tom Schaub has taught at University of California Berkeley and University of Wisconsin Madison. He has been Executive Editor of Contemporary Literature since 1989, and has published widely on Thomas Pynchon, including Thomas Pynchon: The Voice of Ambiguity, and an MLA teaching volume, Approaches to Teaching Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Other Works. He now spends as much time as possible in Maine, and tries to recollect what it felt like back then in the post-sixties lull, when the opportunities society had to offer seemed like threats to his well-being.

Bleeding Edge, p. 406

My Initiation into The Quest

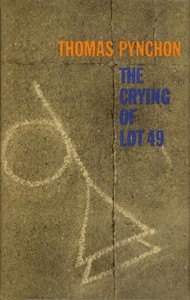

I read my first Thomas Pynchon novel after a day of hiking around Berkeley in 1967. Walking up Grove Street — events would soon change its name to Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd — I saw what looked like a muted trumpet spray-painted on the cement support of an overpass, and a bit further a garbage receptacle stenciled with the word “WASTE.” Someone had added periods after each letter so it looked like this: “W.A.S.T.E.” That evening when I crashed on a friend’s floor I pulled a slim book off nearby shelves titled The Crying of Lot 49 by someone named “Thomas Pynchon.” Very soon I discovered the novel’s plot revolved around the very same graffiti I had seen that day outside. Here they were again inside a novel: the once-knotted posthorn with a mute in its bell, and the acronym “W.A.S.T.E.” I fell into sleep that night wondering how much of the story inside the novel — like the graffiti — was also outside the novel, in my world.Desperately Seeking Pynchon

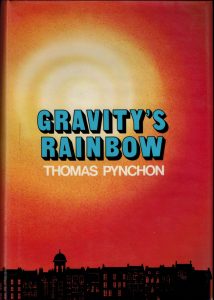

My own stint as a private eye took place at the peak of the mania to find Thomas Pynchon. His first two novels won major awards, but he himself remained stubbornly absent from public gaze or interview. When Pynchon published Gravity’s Rainbow in 1973, a bombshell of a novel that may have been the most unread bestseller ever, it was postmodernism’s answer to James Joyce’s Ulysses, and drew nominations for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. His novels V. and The Crying of Lot 49 had produced a cult following of devoted readers and the literati, but now he was national news. Emissaries from Time Magazine and LIFE went to California but came back empty-handed. In his place, Pynchon sent a comic, Professor Irwin Corey, to receive the National Book Award at the New York ceremony. There are dozens of essays, articles, and websites about the search for Pynchon, but after fifty years, all we have of him are a few pictures. At Pynchon Conferences, movies about him have been shown in which he never appears, the footage mostly clips of places Pynchon may have been. One movie ends with film of an older bearded man looking angrily at the camera. Is that Pynchon?

Every few weeks I visited my director, Sherman Paul, in his office in the English and Philosophy Building, and talked about my reading and the troubles I was having developing a thesis. I always brought along my copy of Gravity’s Rainbow to read him passages. Sherm noted my depression lifted when I shifted from the dissertation to Pynchon’s novel. After about four months of this, Sherm asked me “why not write your dissertation on Pynchon?” The idea that I might write about an author who wasn’t yet dead had not occurred to me. At that point Pynchon had written six short stories and three novels. I walked up College Avenue from EPB that afternoon, a warm wet day during the late January thaw, filled with eagerness to begin again. My peers said I would never get a job with a dissertation on Pynchon, but I didn’t care about a job as much as I cared about finishing — and reading, especially reading this strange new novel with the iconic title.

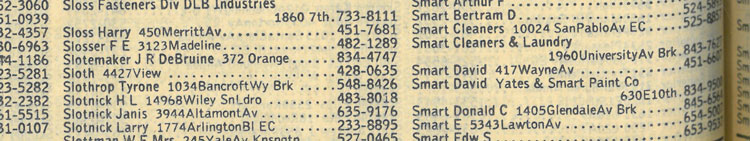

Sherm began to read Pynchon alongside me. At one of our meetings he asked me if any of Pynchon’s character names were “real” names. Benny Profane? Oedipa Maas? Tyrone Slothrop? Herbert Stencil? There is an astonishing amount of daffy arcana in Pynchon’s writing, fact disguised as fiction, but I couldn’t imagine that names like “Slothrop” much less “Blodgett Waxwing” or “Stephen Dodson-Truck” had any counterparts in history or the actual world. This seemed clearly the terrain of allegory and satire, but Sherm’s question stuck with me. That was the beginning of my research in the nation’s phone books. I began at the university library, looking into phone books from the major metropolitan centers, but the only name I found at that time was “Maas,” from the Dutch, a common enough name even in this country. I found no “Oedipa.” After that initial foray, my habit of paging through phone books was something I carried out at odd moments, surreptitiously during slow times at a party, beer in hand, or while visiting friends in cities and towns around the country.

The Quest Heads West

Nearly a year later two friends of mine — Jeffrey Bartlett and John LoVecchio, also in the Ph.D. program at Iowa — and I decided to check out the Modern Language Association Annual Conference, to be held in San Francisco. We expected to be looking for jobs at this same conference the next year, and figured it would be useful to see what the scene was all about. I had a brother living in Berkeley and my parents were flying out for Christmas. During the year just elapsed I had read and reread Pynchon’s novels, and read most of the critical writing that had been published on his work — a most dispiriting task. Someone is bound to have scooped you on this or that insight.

Though Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Claude Levi-Strauss were beginning to transform literary criticism into something called “Theory,” I was at that time a “modernist” reader, interpreting fiction under the protocols of “the new criticism.” The central tenet of this approach assumed a literary text to be a unified work of art. As anyone knows who has tried to read Eliot’s The Wasteland or Joyce’s Ulysses, this unity can be hard to find in modernist writing. The reader must discover this unity by treating literature as an arcane set of allusions and embedded knowledge. T. S. Eliot fostered this kind of reading, perhaps unwittingly, by supplying footnotes to his poem The Wasteland. Modernist writers such as Eliot, Joyce, and Ezra Pound taught us the meaning of literature lies in a structure of coherent meaning implicated within a confusing textual surface. The key to understanding literature lies in deciphering this surface to find the structure of meaning “beneath.” The critic becomes a textual detective. The best reading is one that manages to corral the greatest number of maverick textual details. It is just this modernist protocol that is one target of Pynchon’s satire in The Crying of Lot 49, but it explains my determination to track down every reference, allusion, and symbol in Gravity’s Rainbow. After a year of research I could tell you about the introduction of the New Turkic Alphabet into Kazakhstan, stochastic equations, Herero mythology, and aromatic heterocyclic polymers, but Gravity’s Rainbow didn’t seem to have a structure — I was no nearer understanding the novel.To Berkeley — “Do you think it’s him?”

With our work as TAs complete, the three of us pulled out of Iowa City onto Interstate 80 one late December morning to begin our trip across the Great Plains, through the Rocky Mountains into the Nevada basin and over the Sierras through Donner Pass to San Francisco. Leaving Salt Lake City in the rear view mirror, you feel some inkling of what the first settlers must have felt. Just beyond the Bonneville Salt Flats, Route 80 goes through Wendover, Utah. Then come Wells, Elko, Battle Mountain, and Winnemucca … where the tallest building in town is the tower advertising the price of gas. These are desolate legendary oases to those who drive, who sleep in rest areas or the parking lots of gas stations. There’s a thrilling loneliness to this driving, a realization of the vastness of the United States, and always a worry about an old car breaking down in the middle of the large distances between small towns, on every horizon arid mountains like crumpled rugs. You participate in the national myths of going west, finding one’s destiny by covering new ground, coming to feel a part of the nation by driving through it, by drinking coffee at a dozen or so restaurants, filling up the gas tank. Listening to AM radio all the way.

We arrived at my brother’s house on Edith Street at 6:30 in the morning.

Bartlett and LoVecchio backed out of the driveway as I climbed the stairs to the front door of my brother’s house. David let me in and went back to bed. I was still wired from the drive, so I went into the kitchen and got a pot of coffee brewing. Sitting there in the dim light, listening to the gurgle of the coffee machine, I saw the area phone books stacked on a nearby shelf. I leaned over to pull the Oakland phone book to the kitchen table and began to look. First for Maas, Oedipa. Then for Slothrop, Tyrone. Nothing. Next I tried the San Francisco white pages. Nothing. After a year of looking through phone books I didn’t expect to find any of Pynchon’s character names listed, but the coffee wasn’t yet ready and there was still the 1975 Oakland-Berkeley phone book. The coffee machine was going through its last spasms when fiction and reality came together. There on the page was the name: “Slothrop Tyrone 1034 Bancroft Wy Brk” and a phone number.

Later that morning I showed the page in the phone book to my mother. Just as she had read the sports pages to keep communication lines open with my brother, she was into her second reading of Gravity’s Rainbow. Like me she found it a bit surreal to see the name of a fictional character listed in the Berkeley phone book as an actual person. “Tom Jones” sure, but “Tyrone Slothrop”? Had someone taken Slothrop’s name? And what proofs of identity does the phone company require to list a name? Or was this, perhaps, Thomas Pynchon himself, disguised as one of his characters. I had heard that he made appointments with his publisher using names from his fiction. Or was Tyrone Slothrop an actual historical figure, formerly a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, stationed in London during WWII? Mom and I could barely contain our excitement. “Do you think it’s him?” she asked.

I didn’t know, but as soon as the public library was open I went down to ask the librarian on duty for the last ten years of Berkeley phone books. She gave me a strange look, but disappeared, returning a short while later with a stack. Slothrop I discovered had taken out his phone service only in the year 1975, two years after Gravity’s Rainbow was published. This was disappointing. I had hoped to find that “Slothrop” predated the novel, giving historical substance to a figure upon whom Pynchon had built his character. On the other hand, if Slothrop was Pynchon disguised then it would make sense for Slothrop to appear fairly soon after 1973, as if fiction had created a life.

Though I had Tyrone’s address and phone number, I was reluctant to call. LIFE and Time Magazine hadn’t found him, and none of his friends would give him up. The one thing we knew at that time was the value Pynchon placed on his privacy. The last thing I wanted was to spook the man, to flush him into the public only to have him disappear even more securely in some arcane redoubt. I decided, however, there would be no harm in going under cover to the address listed in the phone book. The Bay Area is often a little cool in December, so I borrowed my brother’s London Fog trench coat for the walk. The sky had dimmed. Particles of mist hung in the yellow light of the street lamps. The search for the 800 block of Bancroft took me west, downhill toward the bay, across Sacramento and then San Pablo, onto the flatland where occupants of the small houses and bungalows were much less white than those in the Shattuck and Vine area where my brother lived. I remembered from Gravity’s Rainbow that Slothrop is sometimes called “schwarzknabe” and I wondered if I were about to meet an African American man in his fifties who would tell me all about the White Visitation and the search for a special V-2 rocket after the war ended.

1034 Bancroft Way — Closer

As I drew near to where the house or apartment should be my heart began to pound. I was a bit damp from the walk, and chilled by the air. But I could not find 1034 Bancroft Way. There was a 1032 and a 1036, but no 1034. Given how elusive Pynchon had proved to be, this seemed to me at the time just right. That’s perfect, I thought. If I returned to the library the librarian would no doubt tell me she couldn’t find the 1975 phone book. In front of 1032 Bancroft was an old black Saab with Massachusetts license plates. In Gravity’s Rainbow Massachusetts is the state of Slothrop’s birth and childhood. In my heart of hearts I could not imagine that Thomas Pynchon or an actual Tyrone Slothrop lived in this area, yet circumstances seemed designed to shake my common sense. The two emotions competed with each other like a pendulum of the mind, my everyday assumptions on the one hand, while on the other an accumulation of details — or were they “clues” — all pointing to the possibility that I had stumbled onto the hideout of the author the national press could not find.

As I drew near to where the house or apartment should be my heart began to pound. I was a bit damp from the walk, and chilled by the air. But I could not find 1034 Bancroft Way. There was a 1032 and a 1036, but no 1034. Given how elusive Pynchon had proved to be, this seemed to me at the time just right. That’s perfect, I thought. If I returned to the library the librarian would no doubt tell me she couldn’t find the 1975 phone book. In front of 1032 Bancroft was an old black Saab with Massachusetts license plates. In Gravity’s Rainbow Massachusetts is the state of Slothrop’s birth and childhood. In my heart of hearts I could not imagine that Thomas Pynchon or an actual Tyrone Slothrop lived in this area, yet circumstances seemed designed to shake my common sense. The two emotions competed with each other like a pendulum of the mind, my everyday assumptions on the one hand, while on the other an accumulation of details — or were they “clues” — all pointing to the possibility that I had stumbled onto the hideout of the author the national press could not find.

When I got back to David’s house, Mom wanted to hear all about it. Do you think he lives there? A mile or more away from the epicenter it seemed even more unlikely. I didn’t know what income his novels were generating, but both V. (1963) and The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) had won major prizes, and Gravity’s Rainbow had made him famous, the subject of front-page treatment in The New York Times Book Review. Why would he be living in a tiny bungalow in a low-income section of Berkeley? It was true that some parts of Lot 49 are set in Berkeley and there was plenty of evidence that Pynchon had been living in California for some years, though at that time no one knew where for sure. “I don’t know,” I told her, but I was beginning to think I should have braved the dog and knocked on the door. I might have surprised him, whoever “him” turned out to be.

I decided to send a coded message on a postcard. “Now that Zhlubb’s gone, what are our silver chances of song?” I signed it “one of the preterite” and included my brother’s phone number. In Gravity’s Rainbow, the character Richard M. Zhlubb — a patent reference to Richard Nixon, who had just resigned under threat of impeachment for his part in Watergate — is manager of the Orpheus Theater in Los Angeles. Slothrop plays a Hohner harmonica but the “harp” falls out of his pocket while he is vomiting into a toilet at the Roseland Ballroom. This passage, early in the novel, describes Tyrone’s harp as “his silver chances of song.” Slothrop in some respects is an Orphic figure of song, who is scattered like the limbs of Osiris — something any graduate student would know who studied the references Eliot supplied to The Wasteland. Late in the novel, but still one hundred and forty pages before the end, Slothrop himself disappears in northern Germany. Slothrop is one of the “preterite,” an important idea that comes from Puritan culture and the theology of John Calvin, who argued that one is either of the Elect chosen for God’s grace or “preterite,” that is, passed over and doomed to hell. Pynchon uses the word more sociologically to identify those whom history has neglected, the poor, and the marginalized — those Michael Harrington termed “the other America.” I hoped that by writing to him in the language of the novel itself, perhaps in “his” language, I might prompt some reply.

I decided to send a coded message on a postcard. “Now that Zhlubb’s gone, what are our silver chances of song?” I signed it “one of the preterite” and included my brother’s phone number. In Gravity’s Rainbow, the character Richard M. Zhlubb — a patent reference to Richard Nixon, who had just resigned under threat of impeachment for his part in Watergate — is manager of the Orpheus Theater in Los Angeles. Slothrop plays a Hohner harmonica but the “harp” falls out of his pocket while he is vomiting into a toilet at the Roseland Ballroom. This passage, early in the novel, describes Tyrone’s harp as “his silver chances of song.” Slothrop in some respects is an Orphic figure of song, who is scattered like the limbs of Osiris — something any graduate student would know who studied the references Eliot supplied to The Wasteland. Late in the novel, but still one hundred and forty pages before the end, Slothrop himself disappears in northern Germany. Slothrop is one of the “preterite,” an important idea that comes from Puritan culture and the theology of John Calvin, who argued that one is either of the Elect chosen for God’s grace or “preterite,” that is, passed over and doomed to hell. Pynchon uses the word more sociologically to identify those whom history has neglected, the poor, and the marginalized — those Michael Harrington termed “the other America.” I hoped that by writing to him in the language of the novel itself, perhaps in “his” language, I might prompt some reply.

The Phone Call – “It’s him”

Christmas Day, Dave’s wife Karen had put in the extra leaf to expand the kitchen table, making room for Mom, Dad, and me, but it made getting around the table difficult. The kitchen smelled of baked ham, rolls, potatoes, and green beans with almonds. She also put out dishes of pickles and olives. Mom had baked pumpkin and mincemeat pies. I squeezed into my seat near the counter, while Mom sat at the other end, by the wall with the phone. We had just begun to pass dishes when the phone began to ring. All conversation stopped. She reached around to lift the receiver off the cradle.

All of us watched.

After a few seconds she said “Just a moment, please,” and turned around with the phone in her lap, one hand covering the mouthpiece.

“It’s him,” she whispered urgently.

While Mom held the phone, a drop of sweat made its way down my spine. In a second or two I might be talking to America’s most famous contemporary author, whose novel Gravity’s Rainbow had been rejected by the Pulitzer Prize committee on the basis of obscenity — a real accomplishment forty years after the Supreme Court had given the okay to Joyce’s Ulysses, and just a few years after Naked Lunch, Howl, and Lolita had been judged by the courts to have redeeming social value. Whatever I said had better be good. I had to be interesting. Mom handed me the phone, the twinkle of a true addict in her eye. Her eyebrows were raised in excitement, as if I were on the line to God.

“Hello,” I managed to say.

“It’s a great song, isn’t it” the voice on the other end said.

I had never thought of Pynchon’s novel — a pastiche of narrative, limerick, elegy, math equations for probability, 760 pages of small dense font, mostly prose — as a song, though without question it was “great.” What was I to say?

“Yes,” I said. “It is a great song.”

“How many times have you read it?”

“Four.”

Suddenly he switched gears.

“Do you play bridge?”

“Do you play bridge?”

“Yes,” I said. I was beginning to feel like Molly Bloom.

“Come over this afternoon at 2:30. We’ll play a few hands.”

“I’ll be there.” There was a click and that was that.

When I hung up I locked eyes with Mom.

“Well? Was it him?”

“I don’t know, but I’m playing bridge with him this afternoon.”

“You don’t think I’m Thomas Pynchon, do you?”

Around two o’clock I left the house to begin my walk to Slothrop’s bungalow. The weather had cleared. The bright sun and cool air etched every edge of leaf and roof in crisp Technicolor, as if the world had become a movie.

When I walked up the driveway I feared the dog, but there was no Cerberus, perhaps a sign that I would be allowed to enter the underworld unharmed. I climbed the two wooden steps, a pair of warped two-by-tens in need of paint, and knocked on the door. I heard footsteps approach and then a voice called out asking my name. “You invited me to play bridge,” I answered. Three deadbolts were unlocked, and the door was pulled back a few inches while a chain still kept the door fastened to the jamb. With the sun reflecting off the white exterior the world beyond the door remained opaque, but out of the darkness came a pointed question: “Are you the man who reads phone books?”

“Yes I am,” I said and with that the chain came off and a tall lanky young man invited me inside.

Stepping through the door frame I noticed I could see directly through the living room and kitchen to a small patch of yard. Beyond the open back door two women muttered chants over an open hole. On a small table nearby two lit candles and smoking incense flickered in the breeze. I wondered if the women were reciting passages from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Behind me I heard Tyrone re-locking the deadbolts.“They’re burying a dead cat,” my host said. “When they’re done we can play bridge.”

“You’re Tyrone?” I asked.

“Yep. I’ll get the cards,” and he disappeared into a back room. He wore a faded blue dress shirt with the sleeves rolled up below the elbows, and a pair of black jeans hung loose on his hips. He padded around in white socks and he looked too young to have been born in 1937. The room I was standing in appeared to be the living room, but it was a small room almost completely taken up by a king-sized bed dressed out in a black sheet. There was just room to walk around the bed on three sides. Black sheets hanging on the walls and covering the windows, which had already been boarded up, intensified the sinister gloominess of the interior.

When the women had finished burying the cat, the four of us took up positions on the bed. Tyrone and I would team up against the women. I had imagined that Tyrone would want to talk about Gravity’s Rainbow, but he seemed preoccupied by bidding and playing. Though I had played bridge since high school and even competed in a contract bridge tournament with my father, I was no judge of Tyrone’s skill, noting only that he played rapidly and with confidence. The women seemed only mildly engaged, and there was little talk unless I brought up a question about Pynchon’s novel. No one mentioned the dead cat. Every hand or so, I asked a few questions. Sometimes I wanted to know the meaning of a particular detail, like the Adenoid Nose that appears early in the novel. Other questions were more broadly thematic, interpretive, such as the importance of race in the novel, or questions having to do with style and literary history. At first Tyrone would provide the briefest of answers; but he soon became impatient with my inquiries, as if their answers were obvious but beside the point.

In the midst of another hand, he looked up from his cards and across at me: “You don’t think I’m Thomas Pynchon, do you?” I had been avoiding that question all afternoon.

“How would I know?” I countered.

He nodded. “You wouldn’t, would you?”

We didn’t bring the question up again and I stopped talking about Gravity’s Rainbow. We continued playing bridge until there was a knock on the door. Tyrone went to the door and exchanged words with the visitors, and then let them in, two men dressed in blue jeans and tee shirts, wearing tennis shoes. They looked like a drug dealer I’d met in college nicknamed “Skydiver” — an anemic guy with ratty, disheveled hair, unshaven. Tyrone disappeared again into the side room and came back dragging a Rubbermaid garbage can. Without being too inquisitive, I saw what looked to be a lot of marijuana packaged in large transparent plastic bags. Tyrone opened one of them and measured out enough to fill two sandwich-sized baggies, giving one to each in exchange for bills of some denomination.

The three of them began to share a reefer. After a period of time I smelled something eerily medicinal that reminded me of my childhood tonsillectomy, and turned about to see one of the guys in the corner sniffing ether from a washcloth. With a lit joint and ether in the same room I decided it was time to leave. Besides, what more was there to learn? I let myself out and walked uphill back to David’s. The low sun of late afternoon flooded the houses on my left in orange light.

“Was It Him?”

As soon as I got in the door, Mom pounced, “Was it him?”

I told her about Tyrone’s question, did I think he was Pynchon. I’d had time to think about this on the way home. Even if it was Pynchon — and the drug dealing didn’t make that any more likely — how would that help me? What would it change? I was still left with his fiction, his words. Should I have asked to see his driver’s license? Tyrone’s answers wouldn’t even advance my dissertation or give my interpretations any more weight. I would have to prove that was Thomas Pynchon down there on Bancroft near the Bay, and do it in some way that would allow me to use him as a source, to quote his words and put our encounter in a bibliography. Even then, I thought, what would I have but the author’s viewpoint? I recalled Kierkegaard’s argument against those who thought belief in Jesus of Nazareth as the Son of God would have been easier if they had lived in his time and known him. This was the “historical Jesus” argument put forward by Bultman. As if encountering him in the flesh would prove that he was the incarnation of God. Kierkegaard thought it would be more difficult to believe, not less.

“No,” I answered. “I don’t think it was him, though I can’t be sure.” I wasn’t sure.

I should care.

A few years later I was living in Maine on the shores of America, in a small fishing cabin just far enough up the hill from Wight Pond that it couldn’t be seen from the water, at least when the leaves were on the trees. Those early months in Maine I bored my new friends with questions about what I should do. All of them had quit jobs in order to lead lives they thought made more “sense.”“You played bridge with Thomas Pynchon!”

This anxious idyll took an unexpected turn when a postcard, as in a bad Elizabethan play, seemed to fall out of the sky from a man named Robert Gillespie: “I lived with Tom Pynchon at Cornell. You can find me at the You Know Who’s Pub in Waterville, every afternoon at 4 p.m.” A week later my job gave me the excuse to visit a group home near Waterville to interview the director, learn about the kinds of children he worked with, and where his funding came from. By four o’clock I had located the You Know Who’s Pub and asked after Robert Gillespie. He called me over to an oak table where he was drinking beer with three other faculty members from Colby College. He told me his former wife had attended a lecture at Yale given by Sherman Paul, and that Sherm had mentioned Gravity’s Rainbow and my dissertation on Pynchon’s work. After the lecture she spoke with Sherm, who gave her my address.

This anxious idyll took an unexpected turn when a postcard, as in a bad Elizabethan play, seemed to fall out of the sky from a man named Robert Gillespie: “I lived with Tom Pynchon at Cornell. You can find me at the You Know Who’s Pub in Waterville, every afternoon at 4 p.m.” A week later my job gave me the excuse to visit a group home near Waterville to interview the director, learn about the kinds of children he worked with, and where his funding came from. By four o’clock I had located the You Know Who’s Pub and asked after Robert Gillespie. He called me over to an oak table where he was drinking beer with three other faculty members from Colby College. He told me his former wife had attended a lecture at Yale given by Sherman Paul, and that Sherm had mentioned Gravity’s Rainbow and my dissertation on Pynchon’s work. After the lecture she spoke with Sherm, who gave her my address.

So I told Gillespie the story of the afternoon I played bridge with Tyrone Slothrop.

When I finished, Gillespie said, “You played bridge with Thomas Pynchon!”

I was dubious. “You think so?”

“Pynchon had a house in Ithaca and sublet rooms to other students. I lived in that house. In his room Pynchon had installed a king sized mattress and made the bed with black sheets. He used black sheets for curtains. What were his teeth like?”

“His teeth?”

“Yeah. He’d spent two years in the Navy and his teeth were a mess.”

I told Bob I hadn’t noticed his teeth. I was sorry. It seemed a long time ago.

“And he looked a bit young for Pynchon, who would have been thirty-eight in 1975.”

“He looked like he should have been in high school when I knew him at Cornell.”

Suddenly he got up from the table.

“I’m going to call him right now.” He went over to the pay phone on the wall. I watched him dial information and talk to an operator, but soon he put the phone back in its cradle and returned to the table.

“The phone has been disconnected.”

“That’s perfect,” I said.

We talked for a while. I’m sure I had a beer. Gillespie told me stories about Pynchon at Cornell. He was well known as the guy who knew everything. Gillespie said he and Pynchon had taken a class on Ulysses together, in which the teacher had assigned each student a page of Joyce’s novel to gloss.

“I showed up on the day I was to deliver the report on my assigned page and I hadn’t done the work,” Bob said. “Pynchon was sitting on the polished granite floor outside the classroom and volunteered to have a look. He proceeded down the page, line by line, annotating references, allusions, etymologies, symbols and so forth.” There was still wonder in Gillespie’s voice as he told the story.

As I drove up the wintry Maine coast that evening the question came alive once more: Had I played bridge with Thomas Pynchon? Was it him?

Slothrop in San Francisco?

In any case, by Christmas of 1979 I was back in my brother’s house again and MLA was being held in the hotels across the Bay. Tyrone Slothrop had disappeared from the Berkeley phone book. I took BART over to San Francisco to track down the hotel rooms where I would be interviewed, but I did not buy a new suit. I remembered the woman at the Hilton and wondered if she was still a working girl. Perhaps because I had reason to be at the conference, I felt less like a charlatan and I found the swarms of well-dressed people milling about less unlikeable. I was still anxious, but in Maine I had a home and friends and I wasn’t all that sure I wouldn’t prefer to be in the woods. I could cut wood for a living if it came to that.

My last interview was on a Sunday morning in the St. Francis Hotel, with faculty members of the Berkeley English department. I took the elevator out of the underground BART station and walked up Powell to Union Square. The St. Francis was on the corner to my left, but I was a good half hour early. Meanwhile I listened to a group of musicians in front of I. Magnin’s playing Christmas music on Jamaican steel drums. My appointment at the St. Francis was nearing when the group began to play Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” The music was calming, and I let its message of spiritual longing fill me with otherworldly perspective. My hands were dry as I walked across the street. Once inside the hotel I saw that I still had five minutes to kill, and by some reflex found the line of phone booths tucked to the left of reception. I opened the San Francisco phone book.

There it was, on Skyline Boulevard. The small perspiration, the prickle on the back of neck, started up again. I still had a few minutes before my interview and I figured I had nothing to lose. I put in my dime and dialed the number. A woman answered.

“Is Tyrone there?”

“Who wants to know?” she asked, hostility in her voice.

“I played bridge with Tyrone four years ago when he lived in Berkeley, on Bancroft.”

“We haven’t seen Tyrone since he disappeared in northern Germany,” she said and hung up.

Life Goes On

The interview with the Berkeley faculty went well. Later that afternoon, the chairman of the English department showed me around campus, introducing me as “our Pynchon man,” and told me a contract would be coming. Sherm wrote to congratulate me: “This will give you something to do with all your energy.” In March I returned to Penobscot to revise the Pynchon manuscript and design a course in contemporary American literature, though the affection for my invented life in the woods only intensified by my decision to leave.

In the fall I started my work as an assistant professor at Cal. Literary criticism had changed. The New Criticism was out. Art was not unified, nor did literature transcend our lives, offering delight and instruction, as Horace had written. Those were the years of the “theory wars” dividing so many departments around the country, and a lot of the theorizing was coming out of Berkeley. One of my new colleagues had made a splash by arguing that Thoreau’s account of Walden Pond is incoherent. There were the New Historicists, too, who argued that literature and the arts, far from being agents of progressive change, are complicit in maintaining the dominance of social and political arrangements already in place. Nevertheless, I was thrilled to have Pynchon: The Voice of Ambiguity appear in print. For me, there was learning to enjoy teaching and the need to begin another book.

Many years that I taught there (and later, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) I put The Crying of Lot 49 on the syllabus in one of my courses. Usually I found time to tell the story of playing bridge with Tyrone Slothrop. I always tried to justify taking the time to share this experience as a commentary on the reason Oedipa’s search can have no conclusion, as a detective novel does. Even so, there were always students who wanted to know if I thought the man on Bancroft had been Thomas Pynchon, though that was never the most important question for me. As the semesters went by — and whether I was meant to teach or to live in the woods by some other means was decided by default in favor of an academic career — the story became a form of communion with those early years when we wonder who we are and think there is a way to be in the world that is waiting to be discovered.

Great piece, great story. Dropped everything as soon as I received the email about the post, and I’m glad I did.

Wish I could take a Pynchon seminar with you.

p.s. Suggest you correct the typo in “1034 Bancroft Way – Closer,” third sentence.

Thanks Lucy! And also thanks for pointing out the typo which is now fixed.

excellent….and hi from Northern Germany, T.P.

Thanks T.P. Always good to hear from North Germany.

Great piece. Took me straight back to the early 1970s when I first read Pynchon and wanted to be a writer like him. A lifetime later, retired in Canberra, Australia, it is time to read Gravity’s Rainbow once again.

Thank you!

Hi – a terrific tale. The Voice of Ambiguity was a must buy when I started reading Pynchon’s books back in 1979. Weirdly was reading through it just the other day. Thank you for bringing that world alive again.

All the best

Martyn

Thanks Martyn. I’m glad that my article here (and my book) brought you pleasure. You are certainly welcome!

Thank you, Tom, for those afternoons in the Rathskeller helping a few young grads puzzle through Gravity’s Rainbow, and for this story, which I still mention to friends whenever they see Pynchon on my shelf and say “Oh hey, is that…?” Maybe all stories are forms of communion. – Chris M.

Good to hear from you Chris. Those times yakking about literature are some of the best.

Fantastic story Tom! Absolutely loved reading it and thanks for sharing! And no doubt … it was Pynchon!

Hi Tom. Glad you liked it. Don’t know why it took me this long to write the story, but now it’s in the clouds!

I enjoyed your story and its own ambiguity. I finished GR about a half hour ago and I’m still in a daze. How long should I expect to suffer from this?

Congratulatiobns, Tom. Haze is apt to last years, if not your life time. Reread your favorite pages.

Pig Bodine approves.

I hope so. One must always seek the approval of the Pig.

Hey, Tom. I just found this through Google. Glad you published it — and spelled my name right lol. I’m 70 pages from finishing Mason & Dixon, which I put off for 20 years. This is what retirement is for. Cheers.

If that’s the guy you met( i.e the photo) then it obviously isn’t Pynchon. Everyone’s seen that photo of him walking his son and watching his son play in his punk rock band.

Not sure what photograph you are referring to. That one of a man and boy on a sidewalk in NYC? That’s been shown not to be Pynchon?

If that were Pynchon I wouldn’t know. All this took place so many years ago. Thanks for reading.

I believe the confusion is in the two Toms. There is a photo of you, Professor Schaub, labeled as “Tom in Iowa City, IA — 1980.” [The photo has been disambiguated -Editor] I believe the reader Yehoo thinks that is a purported image of Thomas Pynchon. No idea what Pynchon looked like in 1980; but I have a clear idea of what Schaub looked like circa 1984—when I was a student at Berkeley—and I can definitely ID that photo. I happen to still have an audio recording of this story being told in a lecture class, with a few interesting but non-significant details that vary. Perhaps as testament to my claim that I am following shelter-in-place orders, I just pulled out an old cassette player to give the story another listen and was reminded of the significant command over timing you had in your lectures. Delivered like a first-rate stand-up routine—I hope you’ll understand I mean that in the best sense possible. (I had permission to record the GR lectures in advance, so nothing untoward.)

Absolutely terrific read, thank you for sharing it with us.

Craig, Newcastle, Australia.

Mr. Schaub: You, and bits of your story have been kidnapped. You are blindfolded and being driven 5507 College Avenue in a maroon Thunderbird. Here, my ex-wife lived with Thomas Pynchon. I do not know, and never met, Tom. However, we enjoyed the same vagina. I took pity on you and your mother. I hope she is doing well. I have been trying start a reunion at 2976 College Ave. You inspired my post: https://rosamondpress.com/2019/11/24/thomas-pynchon-and-i-enjoyed-the-same-vagina/

Enjoyed reading this. Good detective yarn. Have read GR several times, when it came out, and perhaps as I’m now getting closer to endgame, another pass is due. I Youtube posted an ancient recording that tried, musically, to synthesize Pynchon and Farina. It’s searchable using: Lili Marlene dulcimer. I’m the guy in the seersucker jacket. Some poor grammar on the crawl.

The back of my Burning Man vest has a muted coronet over the word Tristero, done in electroluminescent wire. In all the years I’ve wandered the nighttime desert at Black Rock City, no one’s ever noticed. Or at least never mentioned they knew what it meant.

Cheers, ES

So glad I found this article, Tom. I took your Contemporary American Literature class at Berkeley in 1981 or ‘82, where I read The Crying of Lot 49, my first exposure to Pynchon. Pretty sure you didn’t tell the bridge story, but what an amazing story it is!

Best,

Bruce Benway

I had so much fun reading this article. I enjoyed the references to Berkeley locations and odd Pynchon behaviors like black sheets and women chanting over a dead cat. I took your Contemporary American Literature class at Berkeley, too, but 1983-4. My mind wants to connect a few dots of random synchronicity, today’s reading with my son in the Midwest who drove to California once, and a friend who is now an expat living in Berlin. After all, life is more interesting when events have deeper meaning. I hope you and your family are well.

Best wishes,

Pauline F.