Tom Schaub has taught at University of California Berkeley and University of Wisconsin Madison. He has been Executive Editor of Contemporary Literature since 1989, and has published widely on Thomas Pynchon, including Thomas Pynchon: The Voice of Ambiguity, and an MLA teaching volume, Approaches to Teaching Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 and Other Works. He now spends as much time as possible in Maine, and tries to recollect what it felt like back then in the post-sixties lull, when the opportunities society had to offer seemed like threats to his well-being.

Bleeding Edge, p. 406

My Initiation into The Quest

I read my first Thomas Pynchon novel after a day of hiking around Berkeley in 1967. Walking up Grove Street — events would soon change its name to Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd — I saw what looked like a muted trumpet spray-painted on the cement support of an overpass, and a bit further a garbage receptacle stenciled with the word “WASTE.” Someone had added periods after each letter so it looked like this: “W.A.S.T.E.” That evening when I crashed on a friend’s floor I pulled a slim book off nearby shelves titled The Crying of Lot 49 by someone named “Thomas Pynchon.” Very soon I discovered the novel’s plot revolved around the very same graffiti I had seen that day outside. Here they were again inside a novel: the once-knotted posthorn with a mute in its bell, and the acronym “W.A.S.T.E.” I fell into sleep that night wondering how much of the story inside the novel — like the graffiti — was also outside the novel, in my world.Desperately Seeking Pynchon

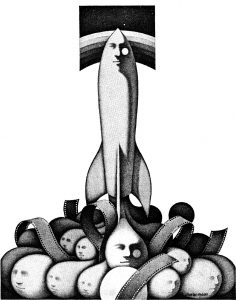

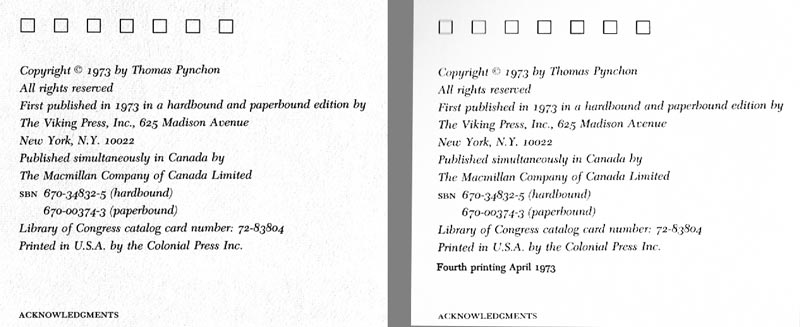

My own stint as a private eye took place at the peak of the mania to find Thomas Pynchon. His first two novels won major awards, but he himself remained stubbornly absent from public gaze or interview. When Pynchon published Gravity’s Rainbow in 1973, a bombshell of a novel that may have been the most unread bestseller ever, it was postmodernism’s answer to James Joyce’s Ulysses, and drew nominations for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. His novels V. and The Crying of Lot 49 had produced a cult following of devoted readers and the literati, but now he was national news. Emissaries from Time Magazine and LIFE went to California but came back empty-handed. In his place, Pynchon sent a comic, Professor Irwin Corey, to receive the National Book Award at the New York ceremony. There are dozens of essays, articles, and websites about the search for Pynchon, but after fifty years, all we have of him are a few pictures. At Pynchon Conferences, movies about him have been shown in which he never appears, the footage mostly clips of places Pynchon may have been. One movie ends with film of an older bearded man looking angrily at the camera. Is that Pynchon?

[Read more…]