By Ali Dehdarirad

I hope I can steal a minute of your time to draw your attention to the publication of my book on our favorite writer: “From Faraway California”: Thomas Pynchon’s Aesthetics of Space in the California Trilogy. The book brings together my passion for Pynchon’s work and my interest in urban and regional studies, dating back to graduate school. Ever since I came across The Crying of Lot 49, I’ve been fascinated by Pynchon’s intriguing fiction, and it is my hope that this book makes a useful contribution to Pynchon studies and the Pynchon community. It is available as an eBook (open access format) on the website of Sapienza University Press. The following is some background on how I came to write my new book. —Ali Dehdarirad

I hope I can steal a minute of your time to draw your attention to the publication of my book on our favorite writer: “From Faraway California”: Thomas Pynchon’s Aesthetics of Space in the California Trilogy. The book brings together my passion for Pynchon’s work and my interest in urban and regional studies, dating back to graduate school. Ever since I came across The Crying of Lot 49, I’ve been fascinated by Pynchon’s intriguing fiction, and it is my hope that this book makes a useful contribution to Pynchon studies and the Pynchon community. It is available as an eBook (open access format) on the website of Sapienza University Press. The following is some background on how I came to write my new book. —Ali Dehdarirad

In “the City Region” with Pynchon

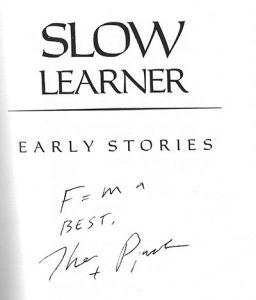

Let me start by sharing some bits of my “Pynchon experience.” I gave The Crying of Lot 49 as a gift to my wife eight years ago, but she hasn’t finished it yet. I think somewhere around chapter three she said something like “that’s enough.” As odd as it might sound, I myself never got to the end of the Italian translation either. On second thoughts, I’ve never read any Pynchon book in Italian because I believe no translation could ever do justice to the complexity and depth of his fiction. My first encounter with Lot 49 is abundant proof of this. I remember reading the first pages of the novel as an undergrad and wondering, What the hell is going on? But it was all exciting. Lot 49 gave me that rush of adrenaline you feel when reading a novel that offers all you need to sit down for long hours and not wanting to leave the book unless the Grim Reaper knocks on your door. Thus began my labor of love with Pynchon, as I stood with Oedipa “in the living room, stared at by the greenish dead eye of the TV tube, spoke the name of God, tried to feel as drunk as possible” (CL, 1). By the time I got to the end of the book, I didn’t want it to finish, as if I had to “keep it bouncing” (CL, 112). Though the novel ended there (or perhaps it never did), it opened up a fresh horizon, enticing me to read Pynchon’s œuvre.