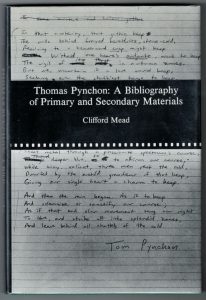

The British literature scholar Cedric Watts once wrote: “One test of literary merit is fecundity, the ability to generate offspring” (xix). More than many other novelists, Pynchon’s work has generated not only literary but also musical offspring: songs, bands, entire albums inspired by Pynchon’s themes and novels. In 1982, Steven Moore made a first attempt to collect such songs and inspirations in Pynchon Notes under the title “Pynchon on Record,” to which Laurence Daw added “More on Pynchon on Record” in 1983 (and later expanded the list on The Modern Word). Sixteen years later, Juan García Iborra and Oscar de Jódar Bonilla published an article that added more names to the previous lists. Since then, the search algorithms on the internet have vastly improved—and so has the amount of available information and the possibilities to upload one’s own material.

The British literature scholar Cedric Watts once wrote: “One test of literary merit is fecundity, the ability to generate offspring” (xix). More than many other novelists, Pynchon’s work has generated not only literary but also musical offspring: songs, bands, entire albums inspired by Pynchon’s themes and novels. In 1982, Steven Moore made a first attempt to collect such songs and inspirations in Pynchon Notes under the title “Pynchon on Record,” to which Laurence Daw added “More on Pynchon on Record” in 1983 (and later expanded the list on The Modern Word). Sixteen years later, Juan García Iborra and Oscar de Jódar Bonilla published an article that added more names to the previous lists. Since then, the search algorithms on the internet have vastly improved—and so has the amount of available information and the possibilities to upload one’s own material.

I wrote a dissertation on music in Pynchon’s work (which I hope to publish soon), and since I believe that no large-scale study on this topic would be complete without acknowledging his musical offspring, I spent many days researching his impact on the music scene. I ended up with a list of more than eighty songs, artists, albums, and record labels who make their nods to the novelist (by the latest update on 14 July 2020, the list has grown to about 120 entries), and I am happy to present it here, replete with links and comments.

The Crying of Lot 49 initially proved to be the most fruitful novel for musical adaptations, likely because its length made it more accessible to readers and because it has been around longer than any other Pynchon novel except for V. However, publishing this blog post and finding more references, Gravity’s Rainbow overtook The Crying of Lot 49. Gravity’s Rainbow’s opening sentence has been used for band names, album and track titles (it’s certainly easier to remember than the opening sentence of The Crying of Lot 49). V. also has a good number of entries but the more recent novels have not received the same kind of attention from musicians. The range of genres covered by these recordings spans jazz (remarkably little), experimental music of all kinds, new classical music, world music, and all sorts of pop/rock subgenres such as rock’n’roll, indie, punk, new wave, or metal. The references range from homages to quotations and from inspirations to adaptations.

Some were recorded by well-known or influential bands and musicians such as Laurie Anderson, Radiohead, Devo, Mark Knopfler, Bill Laswell, or Soft Machine, others by college bands and in bedroom studios. The fact that many of the works of music cataloged are from recent years can likely be explained by the better visibility lesser-known bands enjoy on the internet nowadays, particularly with websites such as Myspace (anyone still remember that?), Bandcamp, Soundcloud, and Youtube. I doubt that it took about fifty years after a novel was released to catch on in the music world. Most artists mentioned are based in Western Europe or North America. Although this may have to do with Pynchon’s popularity in these regions, it is more sensible to assume that I simply did not find artists whose references are in languages other than English. The reason that the adaptations of songs penned by Pynchon are predominantly recorded by lesser known artists may have to do with legal considerations. If little or no money is involved and the visibility of the artist is not so great, the author or the legal departments of the publishing houses may not care to intervene.

On the occasion of some of my New York and Philadelphia talks on the subject in 2015 and 2016 (and the Pynchon birthday party I organized at Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich), musician and poet Tyler Burba interpreted songs from different novels. When I presented my work on Pynchon’s saxophone and kazoo in Atlanta, local musicians Reese Burgan and Caleb Herron accompanied the talk on the respective instruments. There is no telling how many other artists have referenced Pynchon or recorded songs from his books or were simply inspired by his work, but if progeny is a mark of literary accomplishment, these albums, songs, and bands are testament to Pynchon’s wide-ranging appeal as a writer of sonic fiction.

The following list is ordered chronologically, first by novel, then by the work of music. My personal favorites are marked with a magenta heart, thus: ♥. I am certain that I overlooked a great many other examples, so please contribute in the comments section! I will periodically update this post (last update: Jan 16th, 2022).

Contents

1 Introduction (this page)

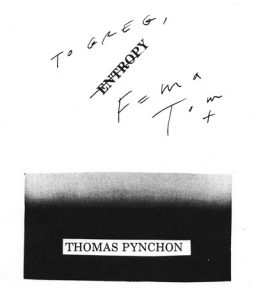

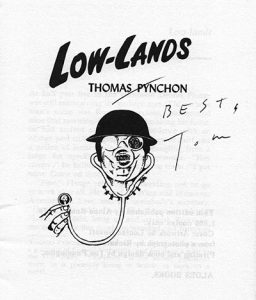

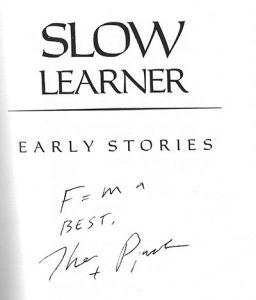

2 “Entropy” and V.

3 The Crying of Lot 49

4 Gravity’s Rainbow

5 Vineland, Mason & Dixon, Against the Day, and miscellaneous homages

6 Bibliography and Biography

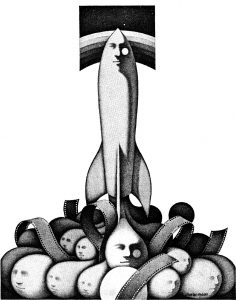

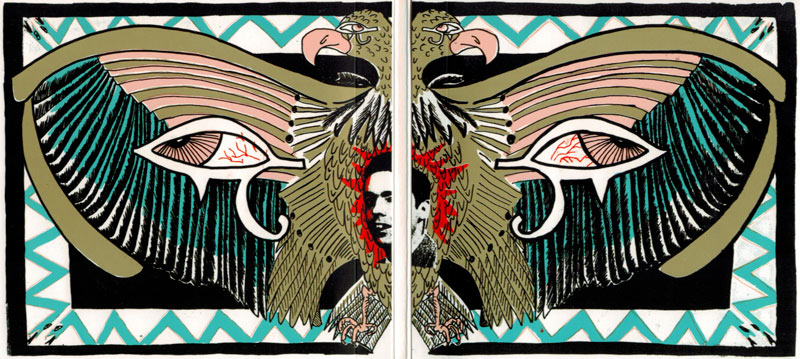

Image credit (top of page): spread-open cover of Land of Kush’s 2009 album Against the Day.